Early Introduction of Allergens

The Rise of Food Allergies

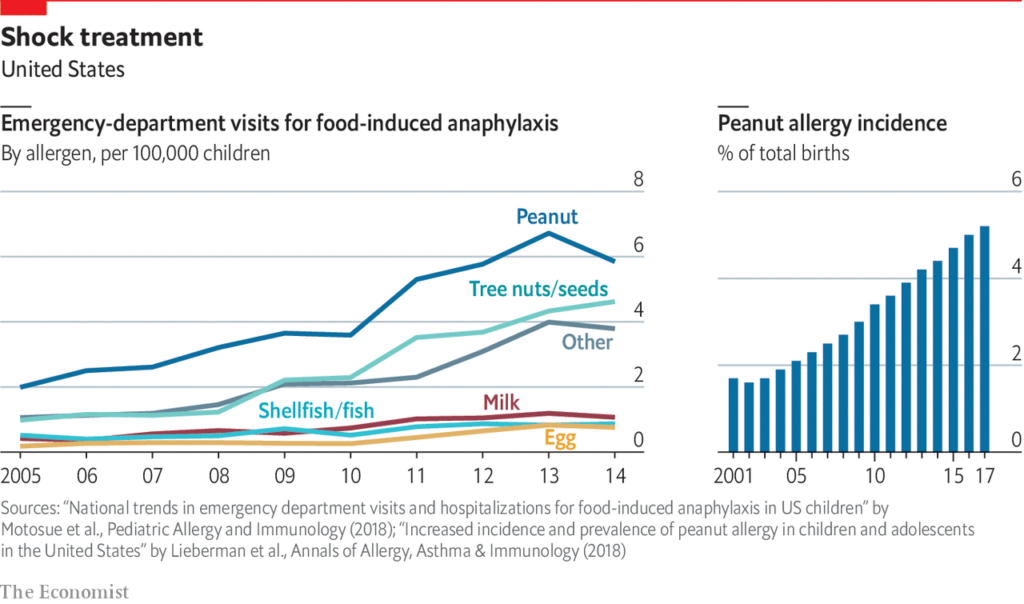

If you pay even the least little bit of attention to the world of nutrition (or school lunch policies, or cafe menus, or grocery stores… ), you probably wouldn’t be all that surprised to learn that food allergies are much more common today than they were even a couple/few decades ago.

Since the 1990s, rates have doubled or maybe even tripled, such that now, more than 10% of Americans suffer from a food allergy (~32 million people) — and about 8% of children do. This mirrors the rising rates of other problems: namely, autism, ADHD, Type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and so on.

Why is this happening?

The quick answer is long, complicated and still up for debate, but generally… the so-called “hygiene hypothesis” holds that kids in the modern world are probably growing up “too clean” for their own good. When kids are under-exposed to germs and what-not (feels weird to be saying this RN…), problems can arise. For instance:

- their developing immune systems don’t get sufficiently stimulated; and

- they aren’t exposed to microbes that humans have, evolutionarily speaking, developed with as a species.

And missing out on these “opportunities,” shall we say, during the critical developmental growth stages of toddlerhood and early childhood may have all the more severe consequences down the road (vs. adolescence or adulthood).

There’s no evidence on it (yet), but we have been wondering if this problem^^ might be exacerbated at present, during COVID times, given that exposure to pathogens has been far lower than normal for the past couple of years.

When you combine the hygiene factor^^ with other individual risk factors (i.e., family history) as well as external triggers (i.e., pollution), it’s not hard to imagine that many, many children’s immune systems are malfunctioning.

Here’s how one of my favorite writers, Michael Pollan (❤️) described it, in a nutshell: “the absence of constructive engagement between microbes and immune system (particularly during certain windows of development) could be behind the increase in autoimmune conditions in the West.”

Fascinating, right? If you want a more detailed look, check out: An Epidemic of Absence: A New Way of Understanding Allergies and Autoimmune Diseases.

BTW, you may be wondering: my baby is barely four months old and doesn’t even “eat” yet, so why are you telling me about this now? *Because believe it or not, THIS is the time (and the only time, really) that you can do anything in terms of preventing food allergies. We’ll tell you…

What is a Food Allergy

A food allergy is functionally the same as an autoimmune response: the body’s immune system misidentifies something as a threat (in this case, a food), and then attacks as if it were under siege from a virus or bacteria (which it isn’t). This is the basis of what causes an allergic reaction.

The Food and Drug Administration’s “Big 8” allergens are milk, egg, peanut, tree nuts, shellfish, fish, wheat, and soy. But among young children, only three culprits comprise more than 80% of all food allergies: cow’s milk, eggs, and peanuts.

BTW, there is no cure for a food allergy — once a person develops an allergy, there’s not much to do about it except manage it… which typically means avoidance of the food altogether. (There have been successful desensitization therapies, but they are expensive and onerous — most people don’t pursue them.) This is why it’s so important to know ahead of time that there are steps you can take toward preventing food allergies.

And we probably don’t need to waste any of your time telling you that a food allergy can take a serious toll on a child’s (and an entire family’s) experience, health, and wellbeing. To put it mildly, it sucks.

Living with Allergies — A Family Affair

Hey — Marissa here, attesting that “it sucks” is right. One of my twins is severely allergic to peanuts, tree nuts and sunflower seeds. Eating out is an obvious challenge (I’m sure you could figure that out on your own, lol) — but the far bigger issue is that her allergies cause us anxiety anytime we leave the house.

What if we come into close contact with someone who just ate peanut butter? What if she’s accidentally exposed to a sunbutter and jelly sandwich at school? What if there’s nut residue on the park bench she sits on? (You can see how wondering about these things can also be mentally… stressful.) We basically have to be prepared for a possible emergency all the time.

And, it’s annoying that we are always “that family” that has to bring our own food to social events (ranging from birthday parties and family dinners to ice cream socials and ‘pancake day’ at the library) — even when everyone is so accommodating. The brutal reality is just that cross-contamination lurks everywhere. So yea, it sucks.

Risk Factors for Childhood Food Allergies

I was surprised to learn that a family history of food allergies is not the only indication of an elevated risk for food allergies. Prior to doing the research for this article, my highly sophisticated understanding of the allergenic risk profile for a kid was this: “Do allergies run in your family? Yes? Shoot, well, you’re f’ed. Oh — sorry, no? Then you’re totally fine!”

Hah-hah… but family history IS a risk factor — a baby with an older sibling who has an allergy has a ~13% chance (vs. ~8%) of developing a childhood allergy.

Yet an even bigger indicator of risk is actually eczema (which many people think is an indication of autoimmunity itself). Among babies with very severe eczema, nearly 70% go on to develop a food allergy, and among babies with mild-to-moderate eczema, roughly a third do. Wow. (For reference, ~10% of babies experience eczema.)

Preventing Food Allergies in Childhood

I feel like there’s a good “DARE-esque” slogan in the making here:

Prevention starts with you, parents. (Sorry, I couldn’t help it.)

Actually, though, food allergies are at least partly preventable, and it’s all about exposure.

You know how for years and years the advice was to AVOID giving babies allergenic foods? Even to the point of advising pregnant and nursing women to avoid allergenic foods like peanut butter? Well — toss that out the window, folks. Much like what happened with safe sleep in the early ‘90s, the research just doesn’t hold up.

In fact, there was never ANY evidence supporting this recommendation — as Dr. Jonathan Spergel, the chief of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Allergy Program, notes, “there has never been any study that proved food avoidance worked to reduce allergies.” If anything, during this exact time period allergy rates rose — not decreased.

As such, and in light of recent studies, the newest evidence-based guidelines advise exactly the opposite:

Exposing babies early on — repeatedly and consistently — to possible allergenic foods can reduce the risk of their developing an allergy by some 80%.

If there was a skincare cream with this kind of effectiveness^^, it would be liquid gold.

The new recommendations, summarized, and agreed upon by virtually every professional medical association on the planet (National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases (and the NIH); The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, the FDA; the USDA; the AAP… really, this isn’t controversial advice, friends), read like this:

Exposing babies to potentially allergenic foods on a continual, sustained basis, over the course of a long stretch of time (meaning, months in a row), starting early (the best time is 4-6 months, which seems to be the critical window of opportunity), can help in preventing food allergies. Think of it as a way of tutoring your baby’s immune system.

This feels counterintuitive to many of us who were raised in homes that abided by the exact opposite principles, but as Dr. Spergel says, “every single study… shows that giving the food makes you less likely to get a food allergy.” And the timing is important, he says: earlier is better than later.

If this advice is making your skin prickle, here are some further notes that may put you at ease: across all the studies conducted on early exposure to allergens, there has never been a severe reaction documented in a baby. There have also not been any reported deaths from a food allergy in an infant under the age of one in all of US medical history — which doesn’t necessarily mean it has never, ever happened, but the fact that there are no records of it at least suggest it would be exceedingly rare. Furthermore, babies are also the least likely age group to have a severe allergic reaction (they’re much more likely to have mild reactions).

BTW — if you’ve already passed the 4-6-month mark, don’t fret, it’s not too late — studies show that introducing allergens even up to one year can still have a protective effect.

Bottom line: It’s important to know what’s coming, and since most parents realistically start solids around 6 months, we wanted to give you a heads up that this should be on your radar. Break out the peanut butter cookies (Kidding — don’t feed your baby sugar. #pleaseandthankyou).

Early Introduction of Allergens: How to Do It

1. DIY.

As with so many things in parenting, there is no instruction manual for this.

At the end of the day, introducing allergens to babies boils down to this advice, from pediatrician Dr. Ronald Sunog: “Eat the [Allergenic] Eight — early and often.” The most important thing is to get your baby these foods, regularly and consistently over time, as part of their solid foods complementary diet. (As Dr. Gideon Lack explains, it’s not a “one and done” proposition.)

*If, however, you are the detail-oriented type and crave more than this, here are some basic guidelines to get you started:

- When to begin: Start whenever you start solids generally (we’ve got the playbook on that here).

- How much: Add small amounts of allergenic foods into other complementary foods, in gradually increasing amounts — you want to make sure you’re using appropriate foodstuffs here, such as:

- bits of cooked egg

- Yogurt, or cheese mixed with puree [*babies shouldn’t straight up drink cow’s milk until they hit the one year mark]

- peanut butter (the smooth kind!) or peanut butter powder mixed into cereal or a puree. Another option is to offer nut-based puffs (such as these organic peanut puffs or mixed-nut puffs from Mission MightyMe).

If you’re not sure “where” to start, Dr. Lack suggests prioritizing dairy, egg, and peanut protein to begin with (because we have the most data on these three allergens).

BTW, in 2015, Dr. Anthony Fauci (then unknown to the masses) said of Dr. Lack’s LEAP trial: “For a study to show a benefit of this magnitude in the prevention of peanut allergy is without precedent. The results have the potential to transform how we approach food allergy prevention.”

- How often: Ideally, you want to have your baby eating these foods ~2x/week, with the goal of maintaining tolerance to the food. Again, “early and often is the key.”

If you desire even more specifics, we turn to the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, which offers these tips:

- Start with about ¼ teaspoon of an allergenic food mixed into your baby’s food/puree (or, if you are particularly nervous, you could rub some of the food on the inside of your baby’s lip as a very initial starting point).

- Watch, and then gradually increase if they tolerate the food well (for example, the following time you could offer them ½ teaspoon mixed in).

Parent tip: consider first introducing allergens on the weekdays — when your pediatrician’s office is open (just to be on the safe side).

Once you’re “up and running,” so to speak, it’s important to make sure you continue to offer sufficient amounts of various allergens on a regular basis, every week. Here’s what Dr. Lack recommends including per week:

- 1 tablespoon peanut butter

- 1 egg

- 1/4 cup dairy yogurt

- 1/2 cup softly cooked whole wheat cooked pasta

- 1 tablespoon tree nut butter

- 1 tablespoon tahini/sesame paste

Remember these foods can all be made “baby safe” by mixing with purees, formula, or breast milk.

So, yes, you can absolutely “do this” (early introduction of allergens) all by yourself. You don’t need anything fancy or special.

“Most children can just have allergenic food incorporated into their diets regularly, without complicated schedules or dosing… The process of feeding babies food does not need to be medicalized or made unnecessarily complicated. Babies should eat all the foods we do — in baby-safe forms — and not have them withheld from their diets anymore.”

Dr. Gideon Lack, Head of Pediatric Allergy at King’s College, London & principal investigator of the LEAP trial

The big advantage with DIY over a supplement (see below) is that you have all the control, and you could introduce any/all of the big 8 allergens (again, that’s milk, egg, peanut, tree nuts, shellfish, fish, wheat and soy) without any unnecessary fanfare.

** If you notice any possible signs or symptoms of allergy, stop feeding your baby and call your pediatrician.

Helpful Products

There are a handful of newer products available that can help you out if you choose the DIY route. (We’re anticipating more of these will hit the market in the coming months/years…)

Mission MightyMe Puffs (designed in consultation with Dr. Gideon Lack, leading researcher in the field and head investigator in the groundbreaking LEAP trial) are puffs that include allergens on the ingredient list — there’s a peanut version as well as a nut butter version, which contains both peanuts and tree nuts. These are an amazing way to work a variety of different nuts into your little one’s diet without any fuss. (Also, show me a baby who doesn’t love puffs…)

Red, Set, Food! also just released its own Baby Oatmeal — it’s organic whole grain oatmeal combined with NINE of the top allergens (the big eight plus sesame). Together, these nine ingredients account for 90% of childhood food allergies. We’re so excited about this because it’s a fantastic, easy way to make sure you’re exposing your kiddo to all the major allergenic culprits.

2. Use a Supplement

The alternative option here is to use a ready-made supplement schedule.

There are a few situations where we see this option as potentially very helpful (all of which might summed up by saying: the convenience factor):

- You have an older child with a severe allergy and don’t want to have potential allergens open/around for their safety.

- *Your baby is at an elevated risk for developing an allergy (mostly, this involves family history and eczema, but you can take a quiz to assess your child’s risk here).

- You don’t want to have to worry about how many times you’ve fed your child X food in a week, but still want to make sure you’re getting them sufficient exposure (again, the convenience factor).

*It’s worth noting that this may feel “worth it,” to many families because — as you will soon find out, babies don’t really learn how to actually eat — whether it’s you who is feeding them or you’re following baby led weaning — for some time after you start solids. So even if you start solids at 6 months, your baby may not be reliably consuming ANY kind of food X times/week, much less a specific kind of food.

- You’re nervous about introducing allergens and want something that’s evidence-based.

Obviously, supplements cost more money, but there are definitely valid reasons to go this route. There’s no reason to think that feeding your baby peanut butter mixed into oatmeal (or whatever) is inferior to a formal supplement, but some parents may feel better with a measured option.

One such option for streamlining the entire process is Ready, Set, Food! It’s clinically designed to expose babies starting as early as 4 months of age to milk, egg, and peanut (which, remember, together comprise more than 80% of childhood food allergies) in a stepwise fashion.

The nice thing about this is that you don’t actually have to be feeding solids regularly to get started — you can throw it in with a bottle of formula or breastmilk and know that you’ve logged your child’s “dose” for the day.

Ready, Set, Food! was formulated with a team of medical experts, and it really follows the studies to a tee. We think it’s a great choice if you want to use a system, as such.

[You can get 40% of your first month with Ready, Set, Food! plus a free gift ($19.99 value) using the code LUCIE40]

Bottom Line:

Remember: you don’t have to go crazy with precision, here. The general pediatric advice is to simply introduce allergens similarly to how you would offer any other food you’re trying to get your baby to “like.” While it might be onerous to hit all the target amounts from the scientific studies, it’s not that hard to add these foods, in small amounts, to whatever it is you’re already feeding your baby a couple/few times a week.

The important thing is that you know that incorporating these allergenic foods into your baby’s diet early on in your starting solids adventure — however you choose to do it — is a good idea. Don’t kill yourself over it. Just do it! And get ready for some sloppy, messy, and fun times coming your way. 😉

My daughter had severe eczema starting from 3 months of age. We used Ready Set Food and it’s fantastic. She has developed a tree nut allergy BUT so far does not have a peanut allergy, which I 100% attribute to Ready Set Food. I wish you could add other allergens to Ready Set Food, but it definitely helped my family. If your baby has severe eczema would also recommend asking your pediatrician for an EpiPen to have on hand. – A physician mom

Sofia — Thanks so much for sharing your experience here! 🙂 RSF is definitely a fantastic option — and we love that you’re a physician-mom supporter. Thanks too for your suggestion about having an EpiPen handy — great note.

It’s worth noting here that sesame is the 9th most common food allergy among children and adults in the US and is increasing worldwide. There are efforts underway to add sesame to the list of major food allergens on ingredient labels. It is a recognized allergen in many countries, including Canada. More info can be found here: https://www.foodallergy.org/living-food-allergies/food-allergy-essentials/common-allergens/sesame

Our hummus-loving family was blissfully unaware of sesame (tahini) as allergen until a dollop of hummus led to an anaphylactic reaction and a trip to the ER for our seven-month old. Now we’re managing, though we fear the presence of sesame could be lurking anywhere–just found out Brach’s candy corn uses sesame oil–what a surprise! As he’s growing up, we have a constant fear that others aren’t aware of sesame as an allergen and may expose our son unknowingly. So, with that said, I wanted to post here to spread awareness of sesame as a top allergen.

Please, please, PLEASE consider working closely with your pediatrician & a pediatric allergist if you suspect your child has food allergies. Our son was born with his milk & soy allergies, making for a very rough first month of breastfeeding as his allergens were passed through my milk (his pediatrician considered allergies rare & unlikely – unfortunately, we were the zebra & not the horse in this Occam’s Razor). Go with your gut & be prepared to seek second & third opinions for persistent symptoms like vomiting, rashes, eczema & hives, sometimes mistaken for cradle cap or acne in newborns.

Jillian, it looks like you may need to check your reading comprehension. The paragraph states that

“ Since the 1990s, rates have doubled or maybe even tripled, such that now, more than 10% of Americans suffer from a food allergy (~32 million people) — and about 8% of children do. This mirrors the rising rates of other problems: namely, autism, ADHD, Type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and so on.”

Nowhere does this article say that ADHD or autism is an autoimmune problem.

Could you explain the 2x/week idea more? (Does that mean some allergen 2x/week or EACH allergen 2x/week, which seems impossible). Mathematically I’ve never understood how that works out (and seen it as the suggestion many other places!). I know most people add about a meal a month (so the first month in solids you’re feeding one meal per day, the second month two meals, and three by the third). So for the first thirty days, I only have 30 meals to work with, and only 7 in any given week. Just focusing on the top 3 allergens, that would mean 6 out of the 7 meals would have to contain allergens to hit 2x/week for each. Or if you’re trying to do all the top 8 (or 9), it’s impossible. I just don’t get the how the “early and often” rule actually looks in practice. Has anyone seen an allergist recommended schedule? I’d love to see a real breakdown of: Week 1 of solids: Day 3 1/4 tsp peanut butter, Day 5 1/4 tsp egg, etc. building up for the first fix months. I’ve never found this anywhere. Any help would be greatly appreciated, I am feeling so stressed by trying to get this right 🙁 This article has been the more helpful how-to I’ve found by the way, thank you SO MUCH!

Thank you for articulating this dilemma! I too and stressed out about what you have described and wished there was more guidance on how to introduce and keep in the diet.