Toddler Feeding Guide

There are a zillion things that we parents do multiple times a day when we have babies and toddlers at home — change diapers, change clothes, swaddle, clean-up messes and toys…

They happen on repeat… But (hopefully, lol) these are temporary endeavors that we will soon (gasp) miss doing.

Not so with one of them, though — feeding.

We will be feeding our kids until they set off on their own (so, like, what, ‘til they’re 32?). Yes — feeding is one of the most constant and… grueling aspects of parenthood. It may change over the months and years, but it’s always there. On a positive note, it’s also something many families look forward to continuing to share even well into adulthood.

For so many, many things, as parents, we feel the urge (need?) to turn to various sources for help and guidance. We rely on what our friends or our own parents or our pediatricians or that book you read last week tell us — but the food “situation” (ahem) in our country right now is such that it often feels like there’s different information coming at you from every angle.

Plus, we don’t, as a nation and a culture, share any unified vision of children’s feeding and nutrition, which maybe isn’t that surprising… Big food companies and lobbyists help to shape nutrition science and guidelines; fast, crappy food is over-available everywhere you look; advertising of said crappy food skillfully targets impressionable young children; and we’re inundated with a glut of conflicting, dated information on what constitutes “healthy eating” on the daily (remember when they used to tell us that fat was a no-no — but don’t worry about the sugar??).

This makes the task of feeding kids even more of a challenge.

But First: How the hell did we get here?

Perhaps you already know some of the story…

In the distant past (think: thousands of years ago), acquiring food to feed a family was super time-consuming (and we think it’s tough now… hah). Hunger was a normal part of life — both pre-civilization and post-civilization. Hunters sometimes returned empty-handed; farms saw bad seasons; shit happened. Broadly speaking, food wasn’t widely available, and the concept of “food choices” would have been entirely alien to most; people had to dedicate a huge proportion of their time and energy to getting enough sustenance.

This meant that feeding kids was (probably) hard, but not in the way we think of it today — kids, as everyone, ate what they could, when they could. They ate what was there. There was no “dinner dilemma” or picky eating; and it’s hard to imagine that adults sat around agonizing over the topic of feeding kids — other than scrambling to make sure there was enough.

Fast forward to the turn of the twentieth century… and things start to look totally different:

Beginning in the early 1900s, and increasingly since then, Americans have been eating more refined (aka processed) foods — especially refined carbohydrates. Because we no longer need to grow, find, or hunt it ourselves, obtaining food takes way less time than ever before in history.

On a logistical level, processing foods has many advantages: it makes foods last longer and easier to transport, it results in more energy-dense food stuffs (read: higher in glucose) and also makes food production and preparation faster, cheaper, and more convenient.

But from a human health perspective, this transition has come at major costs: stripping foods of their fiber and micronutrients; dissociating people from the process of making and getting food; reducing the previous complexity and diversity of the human diet; contributing to skyrocketing rates of all kinds of “Western diet” health problems, including overweight/obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome among Americans; and generating enormous controversy and contention about the question of “how to eat healthy.”

In reality, there are so many ways to eat healthy. Evolutionarily, historically and ethnographically, healthy civilizations around the world have adhered to all kinds of different diets — depending on local climate and ecology, as well as culture — but not so in the modern US. In short, humans have evolved to eat a fascinating variety of whole foods.

Humans have not evolved to eat a western diet of processed foods; and we are not, as a society, healthy. There may not be any one universally perfect diet to follow, but it’s clear that the highly processed diet of America is not ideal, at best.

Let’s not pass that on to our kids.

Of course, the story is more complicated than this^^ — and we’re not suggesting that we simply turn back the clock (or even can) — but we mention “the problem” because it’s hard to fully and completely separate HOW we feed our kids from WHAT we feed them. (Though, as you’ll soon see, we’re going to give it our darndest…)

“Apparently it is easier, or at least more profitable, to change a disease of civilization into a lifestyle than it is to change the way that civilization eats.”

~Michael Pollan, In Defense of Food

We’ve had a lot of parents ask us to extend our baby feeding guides (on breastfeeding, setting up some semblance of a “schedule,” and starting solids) into the realm of the toddler years — and here it is, at long last.

According to parent testimonies, at least 25% of children have feeding problems — and we’re guessing it’s not all smooth sailing for the other 75%, BTW.

Wherever you fall on the spectrum (from its-going-great to holy-cow-what-just-happened), this guide is for everyone, and we hope it is as much a help to you and your family as it has been to all of us in putting it together.

A Toddler Feeding Guide — What you’ll find, and what you won’t

What this guide IS: a go-to source for information and advice about:

- Why it matters how we feed our children;

- What’s reasonable to expect from your child in terms of eating/table manners;

- An introduction to the “division of responsibility” approach to feeding children; and, the main course, if you will —

- How to feed toddlers/children.

Note that we put this guide together for feeding toddlers (usually defined as 1-3 yrs) — but you can actually use and tailor it your own for children at any age. IOW, the guidance and advice here isn’t specific/unique to toddlerhood, and you can continue to rely on these principles beyond then (and/or start implementing them even if your child is older than 3).

What this guide ISN’T: a nutrition handbook. Nowhere here are we going to go into any depth regarding what to feed your child (ok, maybe just a couple of side-notes).

There’s a wealth of incredible resources and information available on this, and every family is so different in terms of circumstances, allergies, preferences, budget, etc. that we’re leaving that to you (for now, lol — maybe we’ll weigh in on this another time). Right now, today, we’re going to focus on the HOW of feeding rather than the what of it.

That said, I can’t help myself from mentioning a couple of notes:

- The most important aspect of nearly every nutritious dietary approach, ranging from veganism to keto to paleo and all the rest, is to eat real (whole) foods.

- It may sound obvious, but kids eat what they like to eat (go figure); serving them good food (would you want to eat it??) can go a long way.

Why Feeding Matters

Babies and toddlers learn SO much about food and eating every single day — and those lessons may stay with them through childhood, adolescence, and even into adulthood.

As many of you may already know, taste preferences are forming during these early years, but so too are eating habits, ideas about food and attitudes toward eating, and the seeds of body image. From the get-go, there’s a lot going on throughout the seemingly simple rituals of feeding.

“How you feed a child is profoundly influential and persists into adulthood.”

~Carol Danaher

In short, to feed children is to teach them, and we parents are the professors.

When they’re devising courses, teachers at every level map out the big picture — they don’t just prep individual lessons, come up with daily activities, or devise assignments on a whim — they have some broader sense of purpose and learning goals into which all of those things not only fit but also contribute.

The same goes for you, as your child’s food/nutrition/eating educator. What do you want your learners to learn? Think about:

- What overall approach toward food do you want to convey to your child?

- Why should they eat?

- Why should they eat certain foods, or avoid others?

- How should they think about eating? Talk about it?

- What are mealtimes like?

Having some answers to these questions will help you implement the suggestions and advice in this guide much more effectively (and with greater resolution).

Parents’ Expectations About Feeding Toddlers — What We Think vs. Reality

To a certain extent, many of us approach the toddler years with somewhat misguided ideas about feeding and eating.

The Early Days: Feeding on Demand and Growth Stress

Personally, I think that many of our misconceptions emanate from the stress that tends to surround feeding and the emphasis we put on *growing* in the first year of life.

When we bring our babies home, we’re taught to feed them on demand (“Yes, whenever! Wherever! Even if it’s 10-12 times a day! The more the better!”), and to feed-them-as-much-as-you-can-so-they-grow (and sleep).

We stress about how much milk they’re getting (because is it really enough?) and how are they progressing on the growth curve, and how much weight have they gained, and dear god will that pacifier ruin my dreams of breastfeeding until they turn X-months-old and how many ounces did they take this time and how many ounces did we make this time… the list goes on.

Here’s the kicker: Nearly none of this translates into toddlerhood.

My point is — we’re conditioned from the beginning to be… edgy about our children’s eating, when what we actually need to do is SETTLE DOWN about our kids’ eating. Because many of the things that we worry about don’t actually make that much sense to worry about. I’ll tell you why…

How Much Should a Toddler Eat

Probably the number one point of concern regarding feeding a toddler is the overall AMOUNT they eat — which may appear either too little or too much. But here’s the thing: we don’t really know how much a healthy, growing child “should” eat.

Yes, there are recommended portion-sizes and daily intake numbers for this and this and this, but the fact is that children can eat far off from those guideposts — in either direction — and still be very healthy.

We all know children who seem to eat endlessly and yet still appear skin and bones (and vice versa). Obviously, there are manifold components that factor into any child’s health and weight (genetics, activity level, diet, etc.)… weight and body type are not solely determined by how much a child eats.

Toddler Weight Curve

Another thing (again, a misperception based on early infancy, when babies are progressively eating more): we assume our toddlers need to be eating more over time.

They don’t.

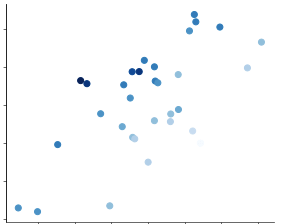

Toddlers don’t ramp up their food intake in linear fashion as they grow. If you like graphs, picture a scatter plot.

Moving on — many of us are under the impression that our children should follow their CDC growth curves like assigned lanes in a track race. This is not how it works. Children don’t necessarily stay in the same constant percentile as they age (though sometimes they do, and that’s great too!). Many children bounce from one curve to another multiple times, and there’s nothing wrong with this. The CDC growth plots are averages, not real-life examples.

Just to be clear — I’m not saying that growth is never a health concern. Of course it is. But we parents are susceptible to obsessing over our children’s status on the growth charts unnecessarily. This is where your pediatrician can help you discern whether there’s actually anything to be worried about.

Most nutrition experts will tell you, the vast majority of toddlers are indeed getting plenty of food; and most pediatricians will tell you, where a child stands on a growth chart can only tell you so much.

Meal-by-meal Thinking and Toddler Nutrition

Similarly, many parents focus on their children’s eating on a meal-by-meal basis, rather than over the long haul. In fact what matters more than any meal or even day is days at a time.

As Stephanie Middleberg (MS, RD, CDN, founder of Middleberg Nutrition and author of The Big Book of Organic Baby Food and The Big Book of Organic Toddler Food) put it, “we adults look at our nutrition over the day — for little children, we’re looking at nutrition from the weeklong perspective.”

This makes sense. Children are using their bodies and their instincts to make decisions about eating — not cultural norms or food plans or any schedule we may set.

For example, telling a child to “eat now so you’re not hungry later” or “no, you can’t have a snack right now because dinner is in ten minutes” is like speaking to them in Latin — it just doesn’t resonate. All they know is that they’re not interested now (scenario 1) or that they are very hungry RIGHT NOW (scenario #2).

Put another way, we adults adhere to cultural norms about when it’s appropriate, what or how much it’s appropriate (or necessary) to eat, etc.

Children don’t.

They don’t care (or even know yet) about what’s culturally appropriate. They’re adhering to (their) biology. And that’s okay!

Toddler Serving Sizes

Related to these notions^^, we have adult ideas about what a plate of food looks like. But a toddler is not an adult and does not need adult-sized portions. (We’re not saying to limit kids to these portions — not at all. Rather, we’re pointing out that we need to let go of our expectations regarding how much our kids eat.)

In fact, as we’ll describe further later on, offering smaller portion sizes (and/or letting children decide their own serving sizes) can be a great strategy to improve mealtimes and eating generally.

Why are we telling you all of this? Much like with discipline, simply knowing what’s reasonable to expect of your toddler can go a long way. The better we can understand how toddlers eat, in real life, and that there is no uniform “normal” amount they should eat, the better teachers we will be.

As Stephanie said, the honest truth is this: you’re not going to have the perfect scenario with your toddler (she’s a toddler). If we accept this up front, we’ll do better down the road.

Here are some other notes that may help you to align your feeding/eating expectations with reality:

As eaters, toddlers are:

- Skeptical — Yes, they are. 🙄

- Unpredictable — Every parent has a story about “that food” their kid LOVES but randomly “doesn’t like” (if you’re lucky the opposite also happens sometimes!). When I serve my kids eggs, I never know what to expect. Some days they tell me they’re — and I quote here — grossy, and other times they’ll eat 6 eggs between the two of them. 🤷🏻♀️ This is very common and is normal.

- Inconsistent — Kids may eat a lot one day (or at one meal) and then eat hardly anything at all at the next; in fact, kids can vary their caloric intake by up to 300% from one meal to the next or day-to-day.

- Opinionated — It’s either cute or infuriating, depending.

- Imperfect communicators — Toddlers don’t… have all the words. They may not know how to tell you something (“I would eat this if only it were a little warmer”) or tell you the “wrong” thing (“I don’t like this” rather than “I don’t want this right now”).

- Carb-seekers — No, it’s not just you. Don’t disparage.

All of this^^ can be immensely frustrating. But it helps, I think, to know that it’s all normal, and it’s all to be expected. Learning about these norms helped me reframe certain things from frustrating-as-hell to par for the course — or even funny. It also helped me have more patience with my kids, because I didn’t interpret a negative response to a dish or an effusive rant about something as a problem with them (my kids), per se.

A couple of other totally normal behaviors you have surely seen (or surely will):

- Spitting out food (and maybe even re-eating it, cool) — This is actually part of the “food acceptance process”; toddlers do it to get comfortable with new foods, and they may even do it repeatedly (as in, up to 15-20 times). So glamorous.

An exercise: try considering this^^ with some empathy. When was the last time you tried a new food? How do you feel about trying new foods generally? How would you feel to try a food without knowing where it came from, what it was, what it might taste like or how it was prepared?

Toddlers have to use their senses to explore foods, and when you really think about it, it’s not that hard to see how they might be nervous about giving it a shot (and/or to be surprised enough about certain tastes and textures to spit something out spontaneously).

- Taking a bite that “doesn’t count” — To an adult, trying something means taking a full bite of it and swallowing said bite. But to a child, trying something may appear the smallest taste, to the extent that it might come across as insufficient (aka “that doesn’t count”)… but it’s not insufficient! It does count! When it comes to tasting, Dina Rose, the author of It’s Not About the Broccoli, says we need to “think micro… A single shred of cheese, one sunflower seed, or one-quarter of a pea are appropriate [tasting] portions.” Jeah.

Another exercise: think about context. We tend to be more conscious and understanding of the fact that our children might not be on their A game if they are tired, hungry, have been cooped up all day, are overstimulated, too hot, too cold, etc. But we almost never take these factors into account when our kids sit down to eat.

Yet, just like anything else, our kids might not “perform” very well at the table because there’s something else going on. Maybe they are tired. Maybe their high chair is uncomfortable. (Experts’ fave is the Stokke Tripp Trapp, btw, because it puts baby at the table right from the start — and we love it too. Abiie makes a near-identical version for about a hundred bucks less.)

Maybe your child is being a grouch and isn’t eating at mealtime because she’s hungry. Sigh. Point being — keep timing and circumstances in mind when things start to derail, and take note of them when they go well (more on this later).

- Playing with food — babies and toddlers play with their food (as a rule, lol), and it’s not necessarily a bad thing. We’ll circle back to this later on, but for now, know that this is to be expected, and that the best thing for you to do is to not really react to it.

A final note here before we dive into the main events: remember that kids are picking up everything, so the ways we talk about food and eating are important. Language is important. A few suggestions from the pros:

- Avoid labeling your child as an eater — don’t say your kid is a “good” or “bad” eater or a “picky” eater. Children pick up on these descriptors and may internalize them.

- Talk about (and ask questions about) food with more depth than “I like it” or “I don’t like it.” Ask: “why do you like it?” or “what do you like about it?” Talk about: taste/flavor, texture, appearance, temperature, smell, other foods a food is like or not like, etc.

- Discuss satiety with more depth than simply “hungry” or “full.” Try to ask questions that prompt your child to describe their physical sensations and state in more detail. (We’ll talk more about some specifics for this in the “how to” section.)

Division of Responsibility: The Satter Approach

The “division of responsibility” framework (DOR) for feeding toddlers and young children is nearly universally accepted and recommended among nutrition experts and pediatricians. (In fact, I learned about it originally from my kids’ pediatrician’s office.) Here’s what it says:

Parents are in charge of the what, when, and where of feeding children;

Children are in charge of whether and how much they eat.

The architect of this framework, Ellyn Satter, named it the “division of responsibility” because she truly thinks about the set-up in terms of the separate roles parents and children play: parents provide food, children do the eating.

These roles are distanced by a hard and firm boundary that is not to be crossed. IOW, it’s two distinct circles, not a Venn diagram.^^

Satter says that problems arise when parents stray outside their role — by trying to do the child’s job (i.e., cajoling children into eating certain foods and/or certain amounts of food), or by letting their kids do the parent’s job (i.e., make the decisions about what to eat).

BTW, experts explain that the reason WHY we shouldn’t give our children control over their menus is simply because we, as adults, know better (or at least, we should…). Think about it: kids are wired to like highly processed carbs and sugar. If we let them dictate the menu, every meal would consist of some variation on chips/crackers/pretzels, candy, pasta/bread/pastries, and perhaps the occasional applesauce, because, you know: fruit.

The truth is that even for adults who don’t necessarily follow an ideal healthful diet, they still know better than their kids what to aim for and what to minimize.

You may hear about parents complaining or joking about being a short-order cook: making their kids a separate mac ‘n’ cheese dinner every night because that’s “all they’ll eat.”… This is the very situation we are trying to avoid.

The beautiful part of the DOR approach is that it recognizes children as capable eaters (they are!) — it gives them the benefit of the doubt and assumes that as human beings, children have instincts about regulating their own eating (they do!).

It trusts that children (yes, even fickle toddlers), actually have their own budding competency we can nurture — indeed, it’s us parents who often have control problems when it comes to food.

“Children have finely tuned mechanisms for determining how much they need to eat, mechanisms that automatically take into account variations in the food they eat as well as in activity, growth, body metabolism, and body chemistry… Your child’s body will regulate if you let it. Your job is to support that process.”

~ Ellyn Satter

Isn’t that refreshing?

When we spoke about this concept of trust with regard to the DOR, Carol Danaher (MPH, RDN, and faculty and board member at the Ellyn Satter Institute) explained it to me like this: we parents trust our children as capable learners in all different aspects of life — walking, talking, reading, singing, throwing a ball… everything.

But we don’t do this with eating.

We don’t trust our children to learn to eat on their own.

We pressure and bribe them, we stress about how much or what they’re eating — and they pick up on this.

We act in ways that clearly show we don’t trust our kids to learn to eat, and they internalize that message.

Remember how patient you were when you taught your child… anything else (LOL!) — you likely expected it to take time and practice and patience. The same goes (or should go) with eating.

“It’s hard to sit back,” Stephanie admitted to me; “it really is… but if you can, it really becomes a beautiful thing.”

The DOR approach also affords toddlers something they want and need as much as air: autonomy. And granting a young child autonomy over their own eating helps diminish the power struggles that so often accompany mealtimes with toddlers.

“The way to get a kid to eat is not to try.”

~Ellyn Satter

If you are skeptical about stepping aside and letting your child sit in the driver’s seat, consider this: does the cajoling/bribing/offering rewards to eat/try a new food/etc. work? Is your strategy leading to improved eating? Pay attention to what happens afterward, and ask yourself honestly: is this helping? “How much your children eat is something they have to decide for themselves,” Dina Rose says. So really, if what you’re doing isn’t working, shouldn’t you consider other options?

“Almost anything parents do to control how much their children eat will ultimately lead to out-of-whack eating.”

~ Dina Rose

The What and When

The other half of this, of course, is that you play your role: decide what food to put on the table and when. This is the piece where you have the control, and you shouldn’t share it.

Like it or not, your child knows better than you what he likes/dislikes, how much he feels like eating, or whether he feels like eating in the first place. So that’s all up to him. But YOU know best what foods to serve, so don’t take orders or let your kids pick the menu.

Taking this a step further, the DOR approach is adamant that we parents don’t cater to our children and their food preferences — in France, as described in hilarious detail in Bringing Up Bebe, there’s not really any such thing as “kid food.” Kids eat what the family eats, which is, ideally, good food (as in, food that tastes good).

There are two sides to the coin here, and both are equally important — when I asked Carol Danaher about it, she told me that the piece most parents struggle with is the concept that their children can choose whether and how much to eat. “But you don’t get the benefits [of DOR],” she said, “unless you maintain both sides.”

Now — much like with discipline or roping your kids into helping around the house, it’s never too late to hit the reset button on your approach to feeding. Whether you’re just starting solids, plodding through the toddler years, or you have school-aged kids and are looking to make a change, you can do it!

Now (finally, phew!), here’s some advice on how to go about this whole feeding business:

Feeding Your Toddler

Remember: you, parent, decide what and when and where to eat — your child chooses if and how much.

The following advice borrows from the Satter division of responsibility, from nutritional experts’ advice, from interdisciplinary perspectives on feeding and nutrition, from cross-cultural parenting practices, and from “real life,” as it were. It’s not a prescription or a strict single-minded approach, but rather a synthesis of frameworks, strategies and hands-on techniques for coming to the table — take it as inspiration rather than dogma, and certainly (as always) pick and choose what works for you. 😉 And have fun!

Follow along or skip ahead to advice on:

- Keeping a predictable routine

- Making mealtimes pleasant

- Staying in your lane (aka, not cajoling your child in eating anything)

- Playing it cool

- Serving tips

- Dealing with panhandling

- Feeding picky eaters and teaching children to love trying new foods

- Adapting expert advice to your family

1. Decide on a predictable meal/snack schedule — establish a routine.

Children thrive when they know what to expect and understand the day’s structure. This applies to feeding as much as anything else. When they know the routine, children are free to work within it (and not worry about what’s coming next and when).

For most families, such a schedule boils down to breakfast, a morning snack, lunch, an afternoon snack, and dinner; but there are also many families who only have one snack, or none at all (more on that below).

Now, we’re not necessarily saying that imposing the 3-meal-one/two-snack schedule is biologically the best scheme here (we’ve arrived at this point rather arbitrarily and more based on cultural and social developments than on human health or certainly science), but for better or worse, this is where we are and what society more-or-less dictates.

In short, getting your kids on this schedule is practical, because it’s the one most daycares, schools, workplaces, and family/friends are going to operate on.

Having a set routine also makes it easier for you to answer questions, because this is the schedule we decided on. Much like using a timer to announce bedtime or clean-up time, having a schedule to fall back on takes the pressure off.

Most young children understand a “schedule” in terms of befores-and-afters, rather than actual times of day — and using this kind of language will likely be a more effective way to communicate the rhythm to them. For example, most kids understand that breakfast happens after they wake up in the morning; you might explain that morning snack comes after playtime and storytime, or that lunch happens after outside playtime, or dinner after evening clean-up (or whatever you like).

*Bonus points if you can rope your kids into the fabric of your mealtime routine — expecting them to help out with food prep, setting the table, and/or clean-up is a win-win because it helps further establish your routine and also teaches them about the work of feeding a family.

Once you decide on a schedule, tell your kids!

Maybe you can even make a project of it — write it on a poster or a chalkboard and keep it somewhere your children can see it or follow along each day. It’s unbelievable how much better children do when we tell them what’s going on (and, depending on their age, explain why). While you’re at it, if you’re giving Division of Responsibility a go, tell your children about that as well.

You might say something like: “Guess what? We’re going to try something new and fun at mealtimes starting this week. I’ll make sure to put out a bunch of yummy things for you to eat, and you get to be completely in charge of how much of everything you have.” (Sell it! And be prepared to get called out — as I did, hah — if you step out of bounds.)

Tips & things to consider:

- Many experts and parents like a “food only at the table” rule, which implicitly cuts back on snacking (and carpet cleaning 😱).

- Along those lines^^, many parents institute a “when you get up from the table, you’re done” rule — and stick to it. It will be painful at first but eventually your child will get the message.

- If your child is often antsy/fidgety at the table, think about staging a quick physical activity right before dinner so they come to the table feeling a little less amped up, or try having them stand at the table.

- Timing: For many of us, dinner can be tough. It’s the end of the day, everyone’s tired, there’s bedtime and tomorrow to think about, etc. — and yet for most this is the main meal of the day. If your child doesn’t seem to be eating well or trying new things at dinner, what if you tried making breakfast or lunch the heavy hitter?

In part, this kind of thing^ depends on your child. If you have a night owl who does well at dinner, great — stick with it. Maybe mornings are so crunched on the weekdays that making breakfast the main meal of the day isn’t feasible, so you do this for lunch on the weekends (or something). It’s just something to think about.

On Snacks

Nearly every expert recommends against constant snacking and grazing. We may think our kids need to snack, but guess what? They actually don’t.

In other cultures, snacking is simply not something that people do (adults or kids). In France and Italy, children usually have a single afternoon snack between meals. It is possible. (In France, Pamela Druckerman writes in Bringing Up Bebe, children don’t even have the right to open the fridge. I love it.)

Here in America, though, it seems like young kids are literally eating around the clock: grazing. Most American parents aren’t going to toss snack time out the window (all the more because our kids become accustomed to it at school and daycare…), and it’s certainly reasonable to have one or two dedicated snack times a day — just try to keep them at least an hour away from the next meal. You want your child to be sitting down for meals hungry.

The Endless Snacking Cycle

Okay — I know I said I wasn’t going to talk about what to feed kids, but it’s near-impossible to separate The Snacking Problem in the US from the fact that so many kids are eating a diet of Goldfish and sugar-laden yogurt. It’s getting out of control — a recent project published in JAMA announced that “ultra-processed foods” constitute TWO-THIRDS of what kids 2-19 years old eat. These foods tend to fall in the high-carb and/or high-sugar category, and they neither satiate nor nourish; and because they almost universally fall high on the glycemic index scale, they inevitably leave children feeling hungrier, sooner.

No wonder our kids are whining to eat around the clock.

Of course, this isn’t an individual thing; it’s a societal issue. As a nation, we haven’t prioritized making healthy food equally accessible. Often, processed and ultra-processed foods are more affordable, practical, and available — especially in certain parts of the country and for certain demographics. It’s a problem.

Another thought on snacking: according to the DOR approach, children get to eat as much as they want for (scheduled) snacks. Indeed, this is the “correct” way to follow the guidelines. In my house, we follow DOR at mealtimes religiously — but not at snacktime.

The reasons are these: snack foods are not meal foods — I’m not putting together a wholesome, well-balanced snack that mimics a meal (I’m just not, sorry); and I also don’t think it’s unreasonable to tell a child “this is what you can have for a snack right now — period.” But technically I’m going rogue here, so don’t take it as an expert recommendation, hah.

Okay — moving on… after a final word of advice on your schedule: yes, consistency is your friend, but so is flexibility. Don’t be afraid to adjust your schedule to accommodate issues as they arise. The schedule should, in fact, ideally allow for some variability.

Here are two examples:

- Imagine your child is regularly very hungry in the afternoons after daycare or an afternoon nap and eats so much at snack time that she never eats dinner. Maybe you decide to consider permanently swapping these (!): serve dinner at afternoon snack time, and have a snack when you’d normally serve dinner. This way, you get your child their actual meal at an opportune moment (i.e., when they’ll eat it) and don’t have to spend the afternoons “doing battle,” as I call it.

- If your toddler is whining for a snack but snack time is still a ways off, maybe you simply move snack time up a little bit. **Don’t “cave” and offer it right now, or while she’s in the middle of a whine-fest, but you can acknowledge that she’s very hungry and offer to see what you can do about moving it up once she’s calmed down. Often, this acknowledgment alone goes a long way.

2. Making Mealtimes Pleasant —

The biggest piece of advice experts have about mealtime is that it be pleasant. It’s not supposed to be high-strung, stressful, or loaded: feeding will go more smoothly when it takes place in a supportive, happy environment. Having a meal is something your child — and you — should be excited about, not something to dread.

Some advice on making this a reality:

- Pay attention! Whether you’re eating or not, be present:

- Put your phone AWAY and limit screens/distractions;

- Try not to multitask (SO HARD);

- Sit down (if you can) with your kids (more on shared meals in a minute);

- Model positivity.

- Don’t make too much of kids playing with their food. In the first place, it’s NORMAL. This is what toddlers do; their learning is sensory, so it’s part of how they explore. *Especially if your child is playing with a new food, consider that a win. It’s engagement, and again, it’s part of the learning process. Remember: at the end of the day, we want them to think food is fun, not stressful.

If your kids show off their food creations, Stephanie recommends staying neutral. “You could acknowledge it,” she said, “but don’t offer positive reinforcement, and don’t be negative about it.”

- On that note: don’t waste your energy mandating perfect table manners for little ones — you can model appropriate table manners, but part of a toddler’s learning to eat is exploring food, which entails touching it, moving it, mashing it, etc. As your child ages, it’s certainly fine to demonstrate and talk about what’s “proper” (HAH), but try not to get too bent out of shape about this.

- That said — there is a difference between “table manners” and “acceptable behavior.” You can and should insist children sit down/attend meals, and that they are “reasonably” behaved (for them) and contributing to an overall pleasant atmosphere.

For the child who says “I’m done” after two bites: It’s reasonable to expect children (even toddlers) to remain at the table for mealtime. Here are some pro tips from Stephanie on keeping them there:

- Use a timer: set up an hourglass timer somewhere visible, so your child can see how much longer she’s expected to remain at the table.

- Invite your child to make a fun dinner playlist with you, and explain that she needs to stay at the table for all the songs (you could also use this to gradually build up — if this is an area of real struggle for you, maybe you start out with only 2-3 songs, then add one each week).

- Do what you can to get your child in the kitchen — the more ownership young children have over food and meals, the more likely they are to appreciate it. (#toddlerswag? hah)

On tantrums at the table —

Having a tantrum at the table obviously detracts from a meal, for everyone. As Carol says, “tantruming at the table is not acceptable.” She advises parents to help the tantruming child leave the table in a calm way, with no anger, for a stretch. You could say something like this: “We like your company at the table, and when you’re ready to be here, we want you to come back;” or “How can I help you? What do you need?”

Table tantrums — like all tantrums — are tough, and at some point they boil down to simple patience. And time.

- Whatever happens, STAY CALM. Stay calm, stay calm, stay calm.

- *If you are anxious about something WRT your child’s eating, he will pick up on that right quick — and it’s likely going to end up contributing to an overall feeling of stress at mealtimes.

- Don’t react to your child — remember all the wacky normal behaviors you should expect, and don’t hold those against them.

- Do not get yourself into a power struggle or a negotiation. You cannot reason with a toddler (as my husband often jokes, “we do not negotiate with terrorists”), and coming to the table with any sort of agenda about what and how your toddler is eating is more likely to backfire than serve you well.

Otherwise, this happens:

Moving on…

3. Thou shalt not cajole your child into eating anything

This is probably the part where we lose some of you — but hear us out! From every corner, experts are telling us: don’t try to “get” your kid to eat anything. Not even one single bite!

In the first place, trying to “get” your child to eat can (and often does) easily detract from your overall aim to make mealtimes pleasant. It can make kids reticent about eating and mealtimes in general. And as soon as meals/feeding become stressful, things can start to deteriorate.

An Exercise in Empathy

I came to see this directive very differently after a recent episode in my house that involved my two kids making their very own batch of “George’s Marvelous Medicine.” Yes, I made the huge mistake of letting them put whatever they wanted from the kitchen into a giant pot, boil it up, bottle it, and label it. (It goes without saying, we’d just finished reading the book together and I thought, How cute! Aren’t they imaginative?)

Whelp, as you may imagine, the resulting concoction was COMPLETELY DISGUSTING. Not to get too graphic, but my gag reflex was kicking in pretty strong. Two things: one, my kids actually tasted it (and liked it enough to ask for an evening dose… geeeeeewwww), and two, when they offered me some to taste I thought, There is no amount of money… and literally had to step away from the scene.

It made me think: what if some proverbial elder forced me to try this?? Or held it up to my face? I just — no [shudder]. Is this how our kids feel when we try to push something on them?

Furthermore, pressuring a child to eat (or stop eating) automatically puts the two of you in the position of being opponents. Who wants that? Not to mention, it threatens your child’s autonomy, and to a certain extent that’s what she’s living for right now, so why challenge it needlessly?

We say “needlessly” because: trying to get kids to eat doesn’t usually work.

In Helping Your Child With Extreme Picky Eating, Katja Rowell and Jenny McGlothlin call this reality the “pressure paradox”: pressuring children to eat backfires.

“The goal isn’t to cajole enough nutrients into a child’s mouth at every sitting. It’s to guide her into becoming an independent eater who enjoys food and regulates her own appetite. If she doesn’t eat enough at one meal, she’ll catch up on the next one.”

~Pamela Druckerman, Bringing Up Bebe

One thing we hear often — the “X many more bites of this” line — is something of a parenting trope at this point. But if you think about it, how could this possibly make any sense to a child? It’s totally inconsistent, as it’s rarely the same amount of bites (and of the same thing). This mandate effectively puts kids in the position of having to ask clarifying questions (how many bites of what? Was that enough? Did that bite count?), because they clearly don’t understand and/or know what we expect of them. And remember, kids do best when they understand the expectations and know the ground rules. Things need to be predictable.

Thus:

- Don’t force your child to finish something or clean their plate (tell that to grandma!);

- Don’t entice them/bribe them/talk them into eating anything;

- Avoid verbiage such as “you have to try it — you’ll love it!” or “this will make you big and strong like a superhero!” or “this will make you mighty smart!” If you’re the type who has to say something, you could just say, “Try it; you might like it.” (Be neutral.)

- Think about it from a child’s vantage: would you want to be bribed/harassed/harangued into eating something?

- Don’t use food as a reward or a way to comfort an upset child — this strategy is linked to numerous unintended and unwanted outcomes, including emotional eating and overeating, and turning certain foods into forbidden fruit. (Personally, I make an exception to this rule with potty training and TRAVEL. Yes, I gave my kids M&Ms when they were potty training. And yes, IMO, food is THE best strategy for making it through travel with little kids. #Sorrynotsorry.) But for everyday life, dieticians consider using food as a way to comfort, reward, or punish your kids “risky.”

- Don’t throw a party when your child tries something — you can acknowledge them or even offer some gentle praise, but don’t blow it out of proportion.

A Strategy for Controlling Yourself, Parents

This piece of the DOR — completely stepping back once you put food on the table — makes many parents uncomfortable. So if that’s you, know that you’re not alone. Members of our team struggle with this too.

When I asked her what she tells parents who aren’t sold on this commandment, Carol Danaher at the Ellyn Satter Institute told me she advises them to do this:

Observe your child’s response to your pressuring them to eat — and really pay attention. Ask yourself — did the strategy work? What was the outcome? Did it improve or deteriorate the mealtime?

Danaher said she even recommends videotaping or recording the scene (!) to watch/listen for any subtle emotional cues that present in such conversations. Most of the time, she said, this kind of tactic elicits a negative emotional response — and that’s not what we want.

Often, parents learn from this simple strategy — careful observation/paying attention — that their “trying to get Jane to eat” approach both 1) doesn’t actually work, and 2) detracts from mealtime.

4. Play it cool.

No matter what happens, be neutral-to-positive, calm, and nonchalant. Don’t be emotional. That’s all.

5. Serving tips

There are some simple tips and tricks in the serving department that can actually make a big difference:

- Serve foods in ways your child can handle them — think about the texture, bite size, temperature, etc. — is it right for her, developmentally?

- Let your child serve herself — yes, really!

I have to say that I was pretty much totally resistant to this piece of advice^^ — but I (reluctantly) tried it anyway, and guess what? It went great! There were ups and downs over time (of course), but there’s no denying that I’ve literally seen the benefits play out in real time:

- I thought my kids would take way too much, but they’ve surprised me by actually spooning themselves less than I would have (everyone told me this would happen, I just didn’t believe them, LOL).

- We’re wasting less food.

- They’re gaining extra practice with fine motor skills.

- They’re learning about polite table behavior because they see that they need to leave some for others, and to ask before taking the last portion of something.

- They can see how much of each dish is left — in my house, we often keep the food behind the kitchen counter, where it’s unseen from the table, and my kids are constantly asking me how much of X is left. I didn’t realize it until we tried self-serving, but I think they were anxious about this, and having everything visible on the table has taken away that uncertainty for them.

- I’m not constantly getting up every two minutes to get them more of things — I can actually just sit and chat with them, and the meal experience has been overall much more pleasant.

A confession: I’ve used the self-serving strategy to “cheat” at DOR. For example: I know my daughter would eat an entire jar of pitted kalamata olives if I put the whole thing on the table. Instead, I put a generous amount in a small serving bowl, and she understands that when that runs out, there’s no more. *As I said, this is technically cheating — it’s not an expert-approved strategy, but I share it with you because I’ve made use of it on occasion with small indulgences at meals or snacks (dates, chocolate, etc.); and I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that at some point, no, you can’t eat the whole jar of olives — not even necessarily because “you can’t,” but because I (or you) might want some tomorrow.

- Serve SMALLER portions. Big, full plates are actually overwhelming to small kids, so serving up smaller portion sizes can help with both under- and overeating.

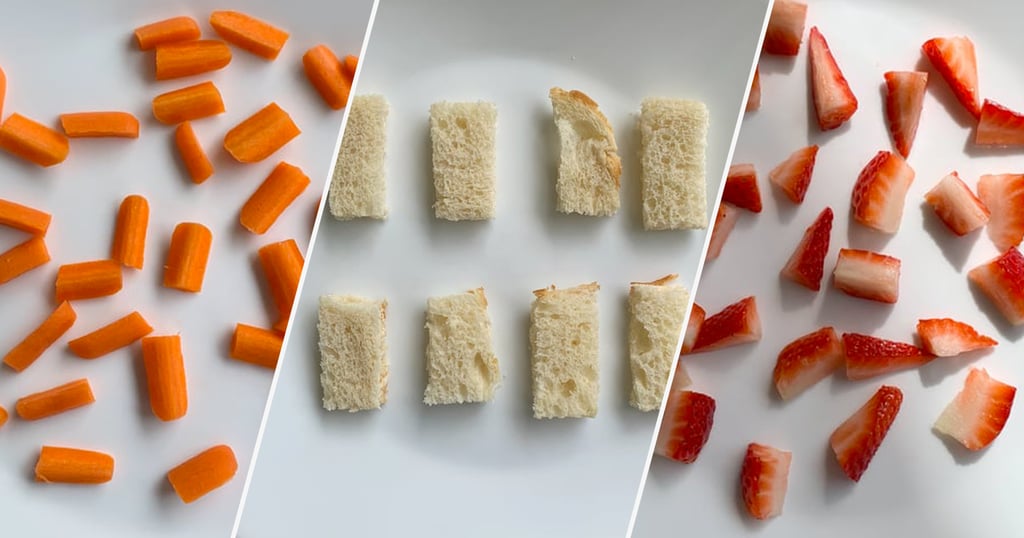

A further note on this^^: If you are struggling with a child who eats almost nothing, try serving almost nothing and see what happens. In It’s Not About the Broccoli, Dina Rose describes how one mother successfully “reversed a pattern of food refusal” by serving up meals like this: four cheerios, 2 blueberries, and 2 bites of egg; three peas, four shreds of cheese, 2 raisins, and a bite of fish. Go figure.

6. When you have a professional-grade panhandler on your hands

As a parent, I am consistently impressed by my kids’ ability to WHINE.

Forget tantrums (though, they are masterful in this arena as well), because I can ignore a screaming kid on the floor as well as the next — but the persistent drone of whining drives me nuts. And I don’t know about you, but food seems to be a major recurring theme. Now, my kids happen to stem from a long line of hangry-headed adults, so they really know how to put on a show when they want something to eat.

IMO, a food outburst (whether it’s whining, crying, tantruming, or what have you) is subtly one of the most difficult to weather, because it’s so easy to give in. I’m like: if I just let her have some pieces of cheese, the noise will stop. It will be quiet (for a few minutes, hah). Wouldn’t that be OK?

But of course experts say this is exactly what NOT to do (well, assuming you don’t want to have a rewind-and-repeat scenario, like, whenever…). Instead of caving to panhandling for food, we are advised to be firm about sticking to designated meal and snack times. And, we are not to let children’s poor responses to a “no” fluster us. A child who has a meltdown about being denied a snack is looking to see what happens — does she get the snack? Does she get more attention (even if it’s negative)? Does she see that she is getting to you?

The advice we all already know and wish was better: Acknowledge, then ignore, friends, ignore—

Until it stops.

Like any behavioral outburst, things are often more painful the first few times this happens, but children do eventually get the message that begging, whining, crying, or screaming for food will not succeed. (There are a lot of parallels with “regular” discipline/tantrums, IMO. And, also as with discipline, staying calm, cool, and collected in these situations can carry you far.)

BTW, if you’re worried that denying your child a desired snack/food is “cruel,” here’s what Ellyn Satter says: it is not cruel (!) — sticking to set routines is part of your job in setting your child up for success with eating. Being reliable is actually helpful, even if your hangry child can’t see that in the moment.

7. Feeding Picky Eaters and Teaching Children to Love Trying New Foods

It’s possible to create an environment that implicitly supports children in trying new foods without violating the central tenet not to cajole/pressure/bribe them into eating anything.

Below are some subtle strategies that can help your child learn to eat new foods — but remember that if/when you try them, you have to be 100% cool with it if your child is still reticent. The goal is to help your child gain confidence and competence eating — not actually to “get” them to eat something or like something.

● Serve a new food paired with something familiar, but not necessarily with a favorite food, because you run the risk of their eating only the favorite food. Think of something your child usually (snort) enjoys but isn’t necessarily “special” (hummus, cottage cheese, tofu, etc.). Stephanie also suggests pairing a new food with a familiar dip to achieve a similar effect.

● Repeated exposure — science shows that we will eventually like a food if we taste it enough (and yes, this is also true for different age groups!). Just because your child doesn’t like something, that doesn’t mean they won’t like it. Keep serving it, and don’t make a big fuss about it. *Remember to let your child try it on their own, as pressuring kids into eating things actually decreases food acceptance. Prepare to persevere, parents — it could take up to 15 times before a child even feels comfortable eating something.

Experts also note that the use of various gimmicks and trickery to “hide” new foods probably doesn’t really help much. That’s not to say you can’t “sneak” some spinach into a smoothie (or something) — go for it! Just remember that this obviously isn’t going to help your child learn to love spinach.

If you have an older child, this “foot-in-the-door” approach can actually be a fun thing to talk about — to stick with the spinach analogy, for example, maybe you talk together about mixing spinach into other foods they like, such as soup or sauce, muffins, scrambled eggs, etc.

● Try serving fruits or veggies as an appetizer — very hungry little children may be more likely to eat them first thing. (Once, in my house, this pre-meal dish consisted of apple slices — highly sophisticated I know — and my children misheard me when I described it to them as an appetizer… and thus this part of any meal is henceforward and forever the Appletizer.)

In fact, serving meals in courses can be very fun (it’s fancy and kids love fancy!) and also work to your advantage (i.e., serving veggies as a first course). Again, this can’t come with any pressure — some kids do really well with this change-up, and others may feel stress at having veggies served first. Here is another place where you can gauge your audience and adjust accordingly.

● Whenever you are serving a new food, make it as predictable and familiar as possible — this entails how it’s cooked/served/seasoned. If it’s your kid’s first time with parsnips, for example, cook and season them the same as you normally do with other vegetables.

● Tell your kids about new foods! Explain what it is and what else it’s like, how it might be familiar or different to them (“This is broccoli, it tastes sort of like spinach and sort of like cauliflower, and when I eat it it reminds me of eating cauliflower, except with a different color and flavor.”), how you cooked it (“I made this broccoli in the oven, just like we normally do with vegetables, and we can season it together at the table the same way you like to season your carrots.”), etc. This simple tactic of delivering information helps build trust at the table and also makes new foods — and tasting them — feel comfortable and safe.

Consider this, from It’s Not About the Broccoli: research shows that young children have certain ideas about how a-food-they-like should look and smell — and they are liable to reject (including without ever having tasted) foods that don’t align with their vision, whatever it is. They probably associate the food with one they think they dislike. (This is SO helpful, right? Because what parent hasn’t said, “but how do you know you don’t like it?! You haven’t even tasted it!” precisely one zillion times.) With this in mind, you can think about the qualities of foods your child likes (color, taste, texture, smell, etc.) and do what you can to make a new food similar.

● Make a game out of your child being a food critic — offer a small sample of something and ask them to tell you about it. Kids eat this up. (Sorry, I couldn’t help it. I’m getting old and I like puns, sue me.)

● Mix up the presentation — use cookie cutters, serve food in mini muffins tins or cupcake liners, cut or slice things differently, etc. These simple changes can seriously appeal to littles. (There’s a reason IHOP started serving Mickey Mouse pancakes, right??) Another idea: chopsticks. So fun.

● Think about timing — many of us incorporate new foods at dinner, because that’s the main meal for most Americans, but often this is not really the best time for our kids. They want to fall into something familiar at the end of the day. Maybe your child would be more open to trying something new at breakfast or lunch, or maybe even at snack time or during cooking time. Figure out the best timing for your child and capitalize on it.

● If you have a child who is super resistant to trying new foods on principle, consider introducing a “new” kind of something you know they’ll like, like a new kind of cookie, cracker, pastry, flavor of yogurt or what have you. The effect we’re going for here is to begin to build a positive association with the actual act of trying a new food. IOW, don’t always make a vegetable or [insert “risky” new food here] the new thing — sometimes everybody needs an easy win.

One other suggestion for very picky eaters is to get them involved with food prep however you can. Whether it’s actual cooking, or grocery shopping, or picking things up from the farmer’s market, the more you can include them in the household food chain, the more willing and likely they’ll be to participate in it.

● On that note, get your kids in the kitchen! When kids have ownership over a dish, they’re much more likely to be willing to try it. (Another lesson I was reminded of with my children’s George’s Marvelous Medicine reenactment…)

Extreme Picky Eating in Toddlers

The root cause of a majority of “extreme picky eating” among young children stems from sensory processing difficulties. Often, this has to do with the texture(s) of a food, which can cause irritation and discomfort besides disorienting or overwhelming a child. (This is one of many reasons why talking to your child about food is beneficial — it can actually illuminate this kind of sensory issue.)

It helped me to wrap my mind around the sensory processing struggles with food to those of noise or crowds: some people aren’t bothered by noisy environments or crowded places (or even like them), while for others, excess noise, background noise, or too many people (whatever that means to you) can be thoroughly stressful.

We are (slightly) more aware of how these other sensory cues — sounds, lights, feeling cramped — affect us (and that they affect us), but we overlook taste. Thinking about how it can drive me bonkers when my kids are excessively touchy at the end of day (while I’m trying to unpack lunches, repack lunches, and get dinner together, say) helped me see more clearly how certain textures or tastes could be irritating in the same ways.

Plus: JELL-O. Gross. But hey, someone has to be eating it, right? Surely they don’t keep making it for fun.

Remember — when it comes to food, little kids are the same as they are about everything else: different. Some children are just by nature going to be more adventurous eaters, and some are going to play the skeptic.

And many kids go through phases.

Your job is to foster a positive attitude toward food and eating and help your child learn to make healthy decisions on their own in time. We can help shape habits and preferences, but temperament and biology play a role too.

8. Adapting Expert Advice to Your Family

Now, much like with breastfeeding/bottle-feeding and purees/baby led weaning, following expert advice or this approach^^ need not be an all-or-nothing thing. You don’t have to pick a team, you don’t have to sign a DOR contract, you don’t have to swear lifetime fealty. We parents often fall into the trap of turning these decisions into binary choices, when in real life, we live in color, not black and white.

The best way to “use” this advice, we think, is to apply it with some fluidity and flexibility, because every child and every family is different. We’re going to drill down on this by taking a closer look at four examples:

- kids participating in choices about foods,

- the “thou shalt taste everything on thy plate” rule,

- “forbidden foods,” and (dunh, dunh, DUHN)

- The Family Meal.

As with anything else in the parenting arena, feeding a toddler is not one-size-fits-all.

On choices —

According to the DOR approach, offering young children choices about food does them no favors — toddlers are still learning to eat what the family eats. But for slightly older children who have learned to eat a wide variety of foods, offering *limited choices for snacks or meals is perfectly fine — it shares a measure of control (and kids love playing their part in decision-making) without sharing too much control.

- Do you want pear or apple slices for your snack?

- Would you rather the potatoes cut and roasted or mashed tonight?

- Should we make fish tonight and lasagna tomorrow, or lasagna tonight and fish tomorrow?

- What do you think, carrots or peppers?

If you’re just coming to DOR, it’s best to start out as the proverbial dictator, but over time, children can be included more and more. Ideally, you’ll continue to expand your child’s role in the menu planning (and meal prep!) as they grow older, with the goal that eventually they’ve learned everything they need to make their own choices about food and be a self-sufficient eater “out in the real world.”

Tip: There are numerous other ways to extend children some autonomy around mealtime:

- Let them choose their own plateware/cup;

- Let them serve themselves and decide what goes where on their plate;

- Let them get their own water/milk;

- Let them help with food prep/clean up (YES THEY REALLY DO WANT TO HELP).

On having to taste everything on your plate —

This is an obvious no-no with the DOR framework, but for many families — and in many other cultures — the “you have to at least taste one bite of everything on your plate” rule works well and doesn’t cause any trouble. As Pamela Druckerman describes in Bringing Up Bebe, in France, children always have to taste everything served. She suggests this: “present the tasting rule to your child as if it’s a law of nature — like gravity.”

For many, this works great. It’s not a huge deal.

For others, though, it stirs up negativity.

Our take? You know your child — if the one-taste rule is something you can implement without it being A Whole Big Thing, go for it! If instead it ruffles feathers or looks to be the first bad move in a game of chess, bag it. (You have plenty of authorities on your side, lol.) If you’re trying to figure out which camp you fall in, use the tool of observation again. Watch closely to see how your child responds to the rule: is it serving your child? Is it improving or detracting from a pleasant mealtime experience?

**PSA: If you try this^^ at home, REMEMBER: a child’s “taste” is not on par with the average adult’s idea of tasting something — even a lick counts! (Yes!) Besides, if you’re at the point where you’re starting to haggle over this, that’s probably a sign that this isn’t working. If it introduces negativity and/or pressure, scrap it.

On forbidden foods —

Experts actually suggest serving treats on occasion (even without limits) so that certain foods don’t become “forbidden foods” and so that children gain practice and experience in moderating their consumption of those foods.

Again, the reasoning here is that you want your child to be able to go off on their own and act wisely (or at least reasonably, lol). If chocolate or ice cream or meat or bread is strictly forbidden, how well could you possibly expect them to handle it when they find themselves in the situation of having unfettered access to [insert disallowed food of choice]? We’d never expect a child to be able to play a sport, or play music, or read or run or climb if we never taught them how or gave them opportunities to practice, so we do have to do that. (That’s what grandparents are for??)

The goal is to raise a human who knows how to eat — we’re teaching these kids how to eat. We have to be teachers, and we have to be patient. It’s all… a process, and it’s always in motion.

On “The Family Meal” —

Ah, the family meal. Here we are. (You thought we’d sneak through this shindig without it, didn’t you???)

You’ve probably heard/read/learned/feared that children who eat family meals with their parents grow up to have lower rates of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, eating orders, and teenage pregnancy; higher rates of academic success and emotional well-being (in high school and beyond); and improved self-esteem, resilience, and happiness.

But wait! That’s not all! Did you know that kids who eat with their families also are 10.2x more likely to get into Stanford, 3.7 times more likely to perform in the Olympics, 7 times more likely to do a good deed for their neighbor, and 4.1 times more likely to invest wisely in adulthood?

Okay — I obviously made up these last bits. But everything else is true — nutritionists have been telling parents to eat with their children for a long time now, and science confirms that there seem to be myriad social, physical, and mental benefits children derive from doing so. (Although, to be fair, these benefits are all correlations — it’s impossible to say with certainty that family dinners themselves are the direct cause…)

All of which is GREAT. Except — “the family meal” is not on the table for so many of us with little children (sorry, couldn’t help the pun), for all kinds of different reasons. We among our team affectionately refer to this as The Dinner Problem.

My point here is not to guilt you into obligatory family meals. I don’t eat dinner with my kids, and I’m not going to sit here and apologize for it. I could tell you why, but I won’t, because I don’t think you need to “explain yourself” either.

The point is simply that it’s hard to deny that eating with your kids does benefit them. As someone who infrequently actually does so, however, I was eager to ask about workarounds — how can those of us for whom the family meal just isn’t going to happen reap some of the benefits of eating together?

Here’s what I learned:

- It need not be dinner — consider whether different timing might work better for your family. For many, breakfast is a lot easier. (Though, there’s also a certain Morning Problem with getting out the door…)

- It need not be all or nothing — if you can’t share a family meal every day, consider whether you can on certain days. Maybe it’s twice a week, or on the weekends, or even once on the weekends. Do what you can.

- Yes, in an ideal world, you’d be sitting eating with your children for a family meal, but just sitting without eating is great too. So maybe you don’t have family dinner every night, but could someone sit at the table for kids dinner?

- Be creative — a family meal doesn’t have to be a picture perfect homemade feast. Maybe it’s leftovers. Or pizza delivered. Maybe you push bedtime back on occasion (or in general, if you want) to make it happen, or maybe you scrap the music lessons that always feel like a chore on Thursday nights.

At the end of the day, there’s what experts suggest and there’s what works for you — however you go forward, please, please, remember, be compassionate with yourself. You can’t do everything. So do what works. And if new foods, or X recommendation, or the family meal, or broccoli simply isn’t happening right now, just think, you’ve got plenty of years left. 😉

In Conclusion–

At the end of my conversation about feeding with Carol Danaher, she mentioned something that really resonated with me: “it takes courage,” she said.

Well, when you put it like this.

Feeding children well takes courage.

Be brave, parents; we’re right there with you.

Stephanie Middleberg is also the author of The Big Book of Organic Baby Food and The Big Book of Organic Toddler Food — two amazing titles that are full of great recipes for littles.

The Ellyn Satter Institute’s website contains a wealth of incredible information about the Satter Division of Responsibility, how to eat and how to feed children; you can also check out numerous other resources like webinars, books, self-study guides and even personal mentoring and coaching via Skype. .

Thanks for all your research on this. This was a lot to take in. I wish there’d been a summary at the end.

While I agree with Ellyn Satter’s DOR approach, this article is problematic because of the weight stigma and food stigma statements throughout. I believe Ellyn Satter promotes intuitive eating generally and health at every size, but you start off by classifying being overweight/obese as a health problem which further contributes to weight stigma and fat shaming. Intuitive eating also recognizes that there is a place for processed foods and sugar just like there is a place for what you term “whole foods” and that we shouldn’t be demonizing any foods with our kids. The article also fails to address the fact that some people, especially low income people, live in food deserts where it is difficult to find affordable fresh food. The goal of intuitive eating is to teach ourselves and our kids body neutrality and food neutrality for an overall healthier existence free from diet culture. While this article cites some of those sources and does a good job of explaining DOR, it misses the overall objective of those teachings.

Amanda,

Thanks for taking the time to comment and I’m sorry that you found some of the threads here to be problematic. It’s 100% not my intention to contribute to the (sexist) stigmatization of fat or body shaming — as a daughter, a woman, and a mom, I know, see and feel the resounding negative effects these have every single day. I too desire to raise my children in a way that rejects the overall diet culture, but I also don’t think that the concept of healthful eating is mutually exclusive with body positivity. Obviously families are going to have differing ideals when it comes to food, and everyone’s approach is therefore going to be different. Based on the medical/anthropological research we conducted for this article, I felt there was/is reason to differentiate between highly processed and less processed foods for health purposes.

Thank you so much for writing this article! In the last few weeks, maybe months now, it has been a struggle to feed our kiddo. Some days he eats everything and more, and some days barely two bites. Of course some of the advice is difficult with a non-speaking child yet, but overall it is so helpful. So thank you! It resonated.

Thank you for this wonderful and comprehensive piece! It’s encouraging and has given me a lot to think about. Question, how do we make sure our children get enough to eat? Tonight I didn’t push food on my toddler when he clearly didn’t want to eat, but then is that it? Do I offer PB&J or something I know he will eat? Thanks 🙂

Mollie, We’re so glad you found something in here that resonates with you! And congrats — it really is so hard to sit back, I know. In response to your question, there are a couple of things I might say. One is just that a lot of families like to make sure there’s always something at every meal you know your child will eat, whether that’s a small side dish or a main dish — this way if they really don’t eat, you know it’s because they’re not hungry. Secondly, some experts recommend having some kind of “always yes” foods that kids can ask for if they don’t like what’s being served — the key if you go this route is to make sure it’s not necessarily a desirable food (the same idea as a time-out doesn’t have to be a punishment but it shouldn’t include anything special like screen time). I do this with my kids, and I love it because we have a set list of five things they know they can ask to have in addition to any meal (not all at once!): eggs, apple slices with peanut butter, hummus, nuts, and tofu. Having the list may seem a bit silly, but it helps with clarity for the kids, otherwise there is a lot of confusion around “why can I have X but not Y.” With the list, if they ask for something that’s on it, I always say yes. If it’s not on the list, I always say no, and there’s no question. (I should note that not everyone “approves” of this strategy, but there are many — myself included — who love it.)

Thank you for this most informative and comprehensive article. As usual, Lucie’s List articles do not disappoint. Your extensive research on the topic is quite evident, and your conversations with multiple respected professionals in the field give us all great “food” for thought (I had to say it, sorry!) and offer up useful suggestions on how to deal with a plethora of issues/concerns surrounding feeding our children. In the end, it is comforting to know we have lots of options and the pathway is ever-changing as a child ages and as his/her palate develops.

Thank you! This was extremely helpful. One question – how do you handle an older toddler (4yo) who claims that besides a few select items, everything else is “yucky”. This likely stems from us giving her too many choices – so do we just serve what is planned and let her be hungry until she realizes there are no other options?

Meghan, I would reiterate up front that I am not a dietician, but some ideas just based on experience and my research… 1. Make sure there’s always something she likes at every meal. You can even put a smaller amount in the serving bowl so it “runs out” quickly, and pair it with other new things. 2. Ask questions — when she says “it’s yucky,” ask her describe why or what she doesn’t like about it. (I’ve done this with my kids and actually learned a lot about their taste preferences, such as that my son doesn’t like slimy things. Good to know, if nothing else.) 3. For the select items, can you switch things up even a *tiny bit? For example, if it’s crackers or pasta (just going with classics here), could you try serving a different kind of cracker or different type of pasta noodle? Often this can help open the door to trying new things more broadly. Let us know how things are going!