Grab A Book!

When my 17-month-old daughter picks out a book to read these days, it’s likely Elmer, the 1968 story of a colorful patchwork elephant by author David McKee.

In fact, it’s almost always Elmer.

We’ve considered hiding it because, sometimes, (a lot of times!), we just need a break. But when my daughter recently pointed to a patchwork rug at a friend’s house, I realized our endless Elmer readings had made an impression.

A baby’s brain develops tremendously during the first three years of life—by age one, it will have doubled in size; by age three, it will have reached 80 percent of its adult volume. And a number of recent studies show the incredible impact of reading, especially reading at home prior to kindergarten.

Here’s why reading is so important and some tips on integrating (more of it!) into your busy day.

Reading to Your Baby or Toddler

1. Start Reading Early

The earlier you start reading to your child, the better.

“It is well-documented that word learning is positively correlated with word frequency and age of acquisition,” writes study author Dominic Massaro, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in a recent study.

Reading typically exposes children to richer language and far more uncommon words than talking since authors must write and rewrite text in order to explain and generate stories. “Most written language has always been very formal, and that’s where you get the challenging language, whereas spoken language has always been very informal, and that’s where you don’t get the quality of the language,” says Massaro.

Take, for instance, author Anna Dewdney’s children’s book Llama Llama Red Pajama. When was the last time you said “fret” or “wail” in everyday conversation? Yet Dewdney manages to use those words in addition to “moan,” “holler,” “stomp,” “pout,” “shout,” and “weep” in the first half of her book to describe a baby llama’s escalating drama.

In a different study, published in Pediatrics in August 2015, researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure the brain activity of 19 preschoolers while they listened to age-appropriate stories through headphones. They found greater home reading exposure prior to kindergarten was strongly associated with activation of specific brain areas supporting semantic processing, or the extraction of meaning from language, and mental imagery, allowing children to visualize or “see” the story.

Visualization becomes even more important as children advance to picture-less books and must imagine what is going on in the text, according to study author John Hutton, MD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, in a press release issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Charlotte Nagy, longtime educator and owner of Charlie’s Corner in San Francisco, remembers reading Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown to her daughter very early on. “I had started reading this book to her the day she was born,” says Nagy. “We went over this story every day, multiple times a day. She had these little bears from Goodnight Moon in her room, and by the time she was eight-months-old, I would say, ‘Where are the bears? Where are the three bears sitting on chairs?’ and she would turn her head and look up at the three bears sitting on chairs because she learned to identify these things [by] the repetition.”

2. Choose Books with Rich Vocabulary

In the 1995 landmark study called “The 30 Million Word Gap,” researchers Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley studied children from three different socio-economic backgrounds: professional, working class, and welfare. They found children from families on welfare hear thirty million fewer words by their third birthday than children from professional families and those children who were exposed to more words had better reading and academic skills once they entered preschool.

This means that the number of different words—not simply the number of words—that children are exposed to matters. “A child’s brain is forever forming and every single word and every different word you say is like a penny in the bank of your child’s brain,” says Erika Cardamone, a licensed speech-language pathologist, founder of The Speechies in San Francisco, and mother of 19-month-old Will. “You’re making a deposit every single time.”

The brain also thrives on repetition. “It’s repetition, repetition, repetition, but then you change it a little bit because that’s what grows the baby’s brain,” explains Cardamone.

For instance, instead of always saying, “Look, the airplane is flying in the sky,” parents should also say the airplane is “gliding” or the airplane is “soaring.” By repeatedly associating the verb “flying” with “airplane” then hearing the new verb “gliding,” babies create rules of language and come to understand that “gliding” must mean something like “flying.” But as the mother of a 19-month-old, Cardamone acknowledges, this is taxing on a parent. “How many synonyms can I find for flying?” she asks, which is why she favors books with rich, challenging vocabulary.

3. Establish a Routine and Aim for a Number of Books

Of course reading to babies is easier than reading to toddlers because babies aren’t constantly moving and trying to climb onto the couch or pour out the dog’s water bowl. But parents can expose toddlers to more language and increase reading stamina, which is the amount of time a child will focus on a book without distraction, by incorporating reading as part of their daily routine.

“It’s all about the routine,” says Cardamone. “For instance, in the morning when we wake up, we are going to brush our teeth and then we read a book. Or, after we eat, and your belly is a little full and you’re calm, we are going to read a book in your highchair. Or bedtime.”

Cardamone likes pairing the activity with the type of book, such as food books (like Amy Wilson Sanger’s Hola! Jalapeño and Mangia! Mangia!) while in the highchair and bedtime books (like Sandra Boynton’s The Going to Bed Book) at night. Keeping stacks of books around the house, such as near the highchair, can facilitate reading.

Cardamone also suggests setting a daily goal of a number of books rather than an amount of time. For instance, aim for three books a day—one in the morning, one before naptime, and one at bedtime. And don’t worry about finishing a book. “If you get your kiddo to sit for a few minutes and read a book, that’s okay. Don’t feel like [you] have to sit and turn the page and finish it,” says Cardamone, “let children do their thing. They are manipulating their environment and learning by that every day.”

4. Read Dynamically

Ever watch an animated master storyteller in action? There’s something to that.

“There’s so much emotion attached to learning,” explains Cardamone, “so it’s important to be dynamic and put emphasis in different places and bring the book to life.” Stressing different words, asking questions, and reading off the page by pointing out different aspects of the pictures are all ways to bring the book to life.

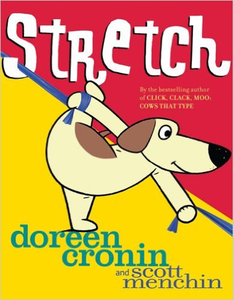

Nagy suggests books with sound, such as Trains Go or Boats Go by Steve Light and Stretch by Doreen Cronin for this reason. “You can create this whole dance” from Stretch, Nagy explains. “The caregiver can interact with the baby, stretching, yawning, and making silly noises and babbling.”

5. Read While Your Child Plays

Can’t get your toddler to sit for a moment? Michelle Sousa Akerstein, former literacy coach and mother of two sons, remembers beginning reading On the Day You Were Born by Debra Frasier to her firstborn on his birth date. And while her approach to reading with him was “textbook,” she acknowledges establishing a reading routine is not as easy with two children. Plus, her youngest does not like to sit still. Her solution? She reads to him while he busily plays with his toys. That way, he can at least hear the richness of the language and occasionally glance up.

The Takeaway

As parents, we cannot be told enough to read, read, read to our children. So in between nap time and snack time, corral your tots (or just let them play!) and grab a book . . . or two . . . or three.

Meanwhile, I guess I’ll read Elmer.

Again.

About Jessica

Jessica Williams lives in San Francisco with her husband, daughter, and a fluffy white dog who thinks he’s human. She is a former English teacher and attorney.

Excellent compilation of research and pragmatics for parents–great work!

Great article, Jessica! Awesome references to the research and great book suggestions! Guess we’ll have to get Elmer on our shelf too!