Recognizing Childhood Anxiety: Symptoms & Signs

It’s important to realize that children — both younger and older — may not have the self-awareness or language to truly understand and name what and how they feel. They probably won’t be able to realize they’re anxious or worried — much less talk about “childhood anxiety symptoms.” In fact, they (and you) may assume they’re just constantly getting sick (headaches and tummy aches, etc.), or perhaps are just “overly cautious.”

This is similar to when your baby is hungry or your toddler is tired; we don’t expect newborns to know they need a bottle or toddlers to realize they are sleepy and need to rest — they cry! They simply don’t yet have this kind of physical, mental, or emotional self-awareness.

We, as their caregivers, must read their cues, assess their needs, and respond appropriately.

It is no different with anxiety.

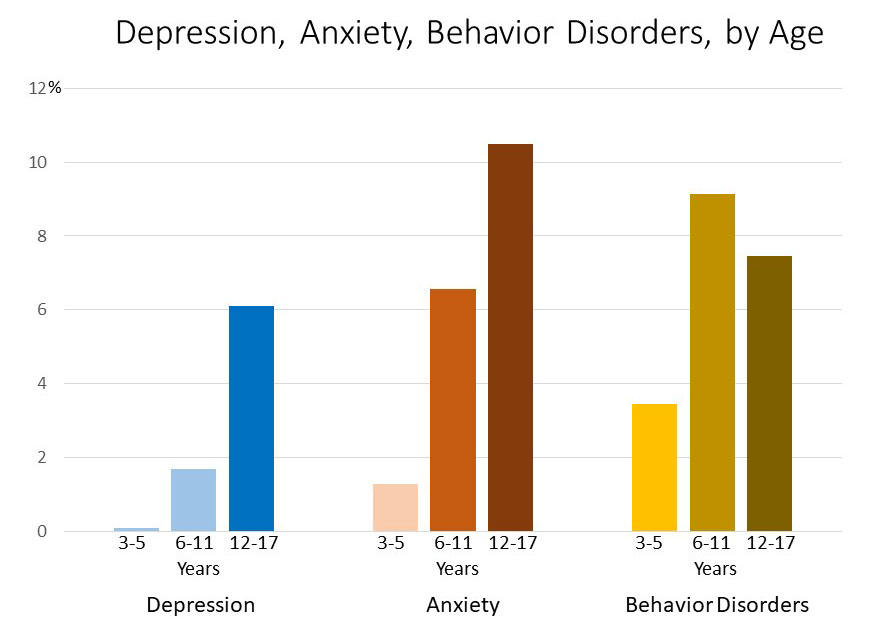

A note on timing: Anxiety disorders can develop gradually over time, or they can erupt suddenly; but most of the time, they appear before the age of 12.

Conor’s Story (as told by his mother)

When Conor was just a tiny little infant, he would scream if I handed him over to anyone else. I always thought he was too young to be experiencing stranger anxiety, but I didn’t know what else it could be. Even now, when new parents hand over their babies for me to hold, I’m always amazed that they’ll come to me without crying hysterically. Conor, now 6, would just never do that.

When Conor was about 2 years old, I began to notice that he acted differently than other kids his age. For instance, at the park, he would refuse to play on the equipment if there were other children there. He just wouldn’t go over and join in, even though he really wanted to. He was so timid and also had a lot of trouble — more than his peers — trying new things. Then, as he grew a little older, he developed this intense phobia of mascots. This turned outings, sporting events, and Halloween into extremely traumatic events for him (and me). Where other kids his age loved dressing up and trick-or-treating, my little boy was so frozen with fear that he couldn’t participate at all.

Conor also struggled with food from the time he started solids. It started as a texture thing — certain textures made him gag or even throw up on various occasions. This created extensive anxiety around food. Even thinking about eating the foods that got him sick made him nervous. When we realized how much Conor’s anxiety was affecting so many aspects of his life, we found an awesome children’s therapist who worked with all of us and taught Conor some highly effective tools to help him manage his anxiety. Anxiety will always be something he has to deal with, but now Conor knows that he’s in control, not his anxiety.

Childhood Anxiety: What Are the Symptoms?

To help you determine if your child may be experiencing excessive worry, here’s a rundown of some of the ways anxiety can manifest itself in children and teenagers.

Physical Symptoms

Anxiety often produces physical symptoms such as tummy aches, headaches, shortness of breath, fidgeting, clammy hands, or a racing heart.

According to the non-profit children’s health resource KidsHealth.org: “these symptoms of anxiety are the result of the ‘fight or flight’ response. This is the body’s normal response to danger. It triggers the release of natural chemicals in the body. These chemicals prepare us to deal with a real danger. They affect heart rate, breathing, muscles, nerves, and digestion (…). But with anxiety disorders, the ‘fight or flight’ response is overactive. It happens even when there is no real danger.”

Emotional Symptoms

If your child is having an unusually hard time managing his or her emotional responses, anxiety might be the culprit. Kids who suffer from anxiety may experience a variety of emotional symptoms, such as crying outbursts, tantrums, clinginess, explosive anger, agitation, an inability to focus, disruptive behavior, and much more.

To further complicate matters, emotional problems can also be a symptom of something greater. When Meg discussed her daughter’s emotional problems with a friend, that friend suggested she be tested for celiac disease — and she was right.

Disinterest

When children suddenly lose interest in activities they previously enjoyed, it can be a clue that they are struggling.

Avoidance

Similar to disinterest, when kids go out of their way to avoid something — such as dogs, social interactions, birthday parties, sporting events with mascots, school, public restrooms, etc. — this can be a sign they are anxious about it.

Needing Constant Reassurance

Constantly seeking reassurance from adults and/or caregivers can be another signal. For instance, children might ask the same question over and over again even after they’ve heard an answer (i.e. “Where will you be waiting for me when school is over?” or “who is picking me up from school?”).

According to Lynn Lyons, LICSW, a renowned psychologist who specializes in childhood anxiety, “when we are little, we get external reassurance (from our caregivers). If reassurance is going to work, it will work in 15 seconds or less… if it doesn’t work within that time-frame, it’s a bottomless pit we can’t fill. When they keep asking and asking the same thing, we know they aren’t getting it — they aren’t processing the reassurance.”

Anxiety Disorders: A Breakdown

Are you afraid that your child’s worries may be preventing him or her from enjoying or experiencing life in a healthy way? While not every person who suffers from anxiety or worrisome thoughts has a diagnosable anxiety disorder, some do. If you’re at all concerned about your child’s mental health and wellbeing, please talk to your pediatrician. He or she will be able to refer you to a child psychologist in your area.

In the meantime, here’s a rundown of some of the most common childhood anxiety disorders:

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Kids and teens with GAD “worry almost every day… and over lots of things… kids with GAD worry over things that most kids worry about, like homework, tests, or making mistakes. But with GAD, kids worry more, and more often, about these things.” [see KidsHealth.org for more]

- Separation Anxiety Disorder: This occurs when kids don’t outgrow the “normal” anxiety and fear associated from being separated from their caregivers. This can mean that kids who struggle with Separation Anxiety Disorder miss many days of school, playdates with friends, extra-curricular activities, or any activity that requires them to separate from their caregiver. They may even struggle to sleep in a room by themselves. Separation Anxiety Disorder is more common among younger children.

- Selective Mutism: Kids with selective mutism may behave and talk normally at home (a place where they are comfortable), yet “refuse to speak in situations where talking is expected or necessary, to the extent that their refusal interferes with school and making friends.” [see the Anxiety and Depression Association of America for more]

- Social Phobia: Children who suffer from social phobia are often hyper-aware of how they think other people are perceiving them. They may be afraid to make friends or speak up in groups for fear they will sound strange or silly. They don’t like to be the center of attention, so they may not raise their hand or participate in class or even detest going to school in general. Social phobia is more common in adolescents and teenagers, as this is the time in life when peer relationships become particularly important.

- Specific Phobia: This is different from being a little afraid of something. When people are around something (or even think they may be around something) they are phobic of, they experience extreme and paralyzing fear and panic.

“With a specific phobia, kids may have an extreme fear of things like animals, spiders, needles or shots, blood, throwing up, thunderstorms, people in costumes, or the dark. A phobia causes kids to avoid going places where they think they might see the thing they fear. For example, a kid with a phobia of dogs may not go to a friend’s house, to a park, or to a party because dogs might be there.”

KidsHealth.org

First Steps at the First Signs of Childhood Anxiety

We’ll delve into the specifics for how to respond to and control childhood anxiety (not cure it) in the next two segments, All About the Worry Cycle and How to Help — but in the meantime I wanted to throw out a couple of things you can start to work on right away because they are at the foundation of getting through (and hopefully over!) your family’s anxiety issues:

Step One: Taking Care of You (I’m looking at you, anxious parents!)

If you are a parent who has anxiety or tends to catastrophize (raising my hand here), it’s important to know that this likely does trickle down to your children.

No blame intended here — again, I’m a type-A worrier by nature who suffers from anxiety myself, but it IS important to be aware that we are always modeling behavior (whether we want to or not) for our kids.

Awareness of your own behavior/tendencies is the first step here.

According to the Child Mind Institute, a non-profit that works to help children and families struggling with mental health and learning disorders, parents can pass their anxiety on to their kids: “Kids look to their parents for information about how to interpret ambiguous situations; if a parent seems consistently anxious and fearful, the child will determine that a variety of scenarios are unsafe. And there is evidence that children of anxious parents are more likely to exhibit anxiety themselves, a probable combination of genetic risk factors and learned behaviors.”

Therefore, the first step in helping our kids with their behavior is to learn how to better manage and tolerate our own stress and anxiety.

How to Manage Our OWN Anxiety

Unfortunately, keeping our own anxiety in check is no easy task. If it were, we’d all be stress free (and my therapy bill would be far less, ahem, expensive…).

True story: I’ve been working on managing my own anxiety for almost 40 years. After some seriously panic-stricken years (you know, with two pregnancies, two bouts with postpartum depression, raising twins, etc.), I’m finally in a much better place in which I accept my anxiety as a part of me, but know that it isn’t me and doesn’t control me.

I’m able to challenge my worrisome thoughts — i.e. what’s the probability that [name any anxiety-provoking thought here] will actually happen? And if that thing DOES happen, can I handle it? (Hint: the answer is usually yes…) Do I have any control over whether or not this thing happens? If not, I’m going to try and let the worrisome thought go. If yes, I’m going to take whatever preventative measure is reasonable, and THEN I’m going to let the worrisome thought go.

Therapy has proven very effective for me, and I’ve found the book The Worry Solution to be exceptionally informative, easy to digest, and chock-full of helpful tips on managing my anxiety.

For some easy things you can do right now to help manage your anxiety, check out these tips from the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, which offer ways to calm your mind and body:

Step Two: Being Loving and Affectionate With Our Kids

Research shows that the children of loving and affectionate parents are less likely to experience symptoms of stress, hostility, anxiety, depression, etc. as they grow older. This is likely due to the fact that when we are in emotionally and physically close relationships with the people we love, our bodies release oxytocin (the “feel good” hormone). It’s responsible for many of our warm, fuzzy, positive feelings (with the exception of labor contractions, LOL), and it also helps children learn they can trust in unconditional love and support from their caregivers. This, in turn, helps kids to build confidence, emotional resilience, and a healthy sense of attachment.

Note that we don’t have to make big, huge grand gestures to show our kids they’re loved. All it takes are little moments of affection: breast or bottle feeding, hugging, infant massage, being truly present with our kids when we play, really listening to them, etc. I’m constantly amazed by how little it takes to overwhelm my children.

Step Three: Be Open with Your Kids about Your Own Anxiousness

Although it might seem counterintuitive to talk to your kids about your anxious feelings, experts suggest this is exactly what you should do. Lynn Lyons, LISCW says being open and transparent about your own struggles is key. When you do this, you’re modeling emotional self-awareness and healthy coping mechanisms for your kids.

According to the Child Mind Institute, “while you don’t want your child to witness every anxious moment you experience, you do not have to constantly suppress your emotions. It’s okay — and even healthy — for children to see their parents cope with stress every now and then, but you want to explain why you reacted in the way that you did.”

All in all, know that it’s perfectly acceptable for our kids to see us experiencing and handling all kinds of emotions and struggles. It’s HOW we manage them — and teach our kids to manage their anxieties — that counts. (You can read more about that in part 4, How to Help.)