Good Enough Parenting

My two children were barely 2 and 4 when the pandemic started, and in the wake of months of staying-at-home, remote work, and closed schools/day care, I remember not entirely connecting with a silver-lining message I was hearing from everywhere. I’m sure you heard it, too: that despite everything, it was nice to hit the pause button; to recenter; to not be running around from one activity to the next, the weeks passing by faster than the hours.

You see, at that point, I hadn’t yet gotten on the hamster wheel. My kids went to daycare/pre-K, and that was pretty much it. It was easy to look at other families (most of them with older children) whose lives seemed unnecessarily packed to the brim and think: we’ll never be like that.

Oh, how easy it was to sit high and mighty! (Yes, you can and should laugh at me…)

Fast forward to this spring, in the middle of planning a get together with a friend sometime after school (a seemingly impossible task), I suddenly realized that our afternoons were getting busy. Like, real busy. I had hopped on the carousel and I didn’t even know it.

Shoot.

The problem is, I dove in not because I felt I needed to pad my children’s resumes — I’m not (yet) stressed about college admissions — but simply because I heard people talking about all these activities their kids were doing, and I thought my kids would enjoy them too.

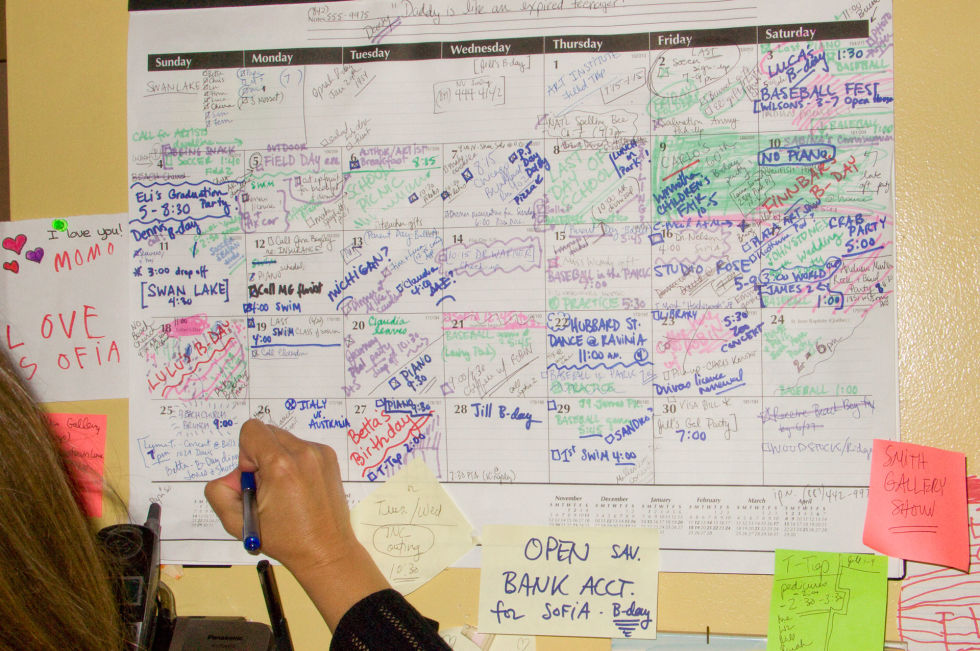

We signed up for swim lessons because, safety. We’re doing tee ball because my kids love it and it’s great to be outside. My daughter is taking dance classes because she’s a diva. Birthday parties are back now, so there’s one of those nearly every weekend… Right in the middle of looking into gymnastics and tennis and tumbling and oh, piano lessons too, it hit me: I’m going to have to proactively curtail all of this.

Here’s the thing — I really, really don’t want to be a helicopter mom. I DON’T. I am an ex-academic who has read all the things about all the ways that [modern society/intensive parenting/digital technology/overscheduling/underestimating our children] are harming our children. I don’t want to schedule every minute of my kids’ (our?) lives; I don’t want to plan or do everything for my kids; and I don’t want to fall down the rabbit hole where we feel the need to keep up with everyone else’s extracurricular pursuits.

I want to be the kind of parent who lets my kids do things for themselves, that gives them time and freedom to play and be bored and do things on their own — I just never quite appreciated how hard this would be.

Turns out, it’s really freaking hard. SO FREAKING HARD.

As it happens, none of this unfolds in a vacuum…

The ideal of so-called intensive parenting is a relatively new phenomenon (as in, of the last 25 years or so) and it’s distinctly American.

Without getting too far into the weeds (if you want that, see here, here, here, here, or here), let’s just note that the latter half of the 1900s saw a *huge proliferation in advice aimed at parents (about how to raise kids), and that the very idea of parenting as a “thing” or “action” (aka, a verb) started to come into vogue in the U.S. around the 1970s. In the following decade, A LOT of newfound fears and anxieties surrounding children’s safety echoed from every corner, and this ultimately helped lead to lasting changes in parenting habits and norms over the subsequent decades.

Fast forward to the twenty-first century, and American parenting has a distinct brand of “contagious anxiety.”

Can you feel it?

“‘Intensive parenting is a type of parenting that requires a significant amount of time and money,’ says Patrick Ishizuka, a sociology professor at Washington University in St. Louis who studies intensive parenting. It includes scheduling children for multiple extracurricular activities, as well as advocating for their needs and talents in communications with schools and other institutions. And it’s not limited to a small subset of parents. ‘I would describe it as the dominant cultural model of parenting in the US right now,’ says Ishizuka.” ~ BBC

Numerous scholars and media outlets have unpacked the complicated ways in which the central defining features of intensive parenting are tied up with higher education, class aspirations, women’s changing roles in society and income inequality, not to mention other constantly changing landscapes: the workforce, the economy, college admissions, geographic mobility, and now, the pandemic…

Intensive parenting may be circumscribed to the middle- and upper-classes, but it impacts everyone. Timed with the rise of intensive parenting, income inequality and educational access gaps have worsened. Parents — especially mothers — are spending more time actively caring for their children, like driving them to and fro, playing with them, helping with their homework, etc., compared to decades past… and still we all worry, is it good enough?

The Two Halves of Intensive Parenting

There may be as many ways to parent intensively as there are zip codes — it’s not a monolithic kind of thing — but from our vantage, there are really two main threads to the anxieties underlying it:

- Literal fear — aka That Dreadful Horror that something could happen to your child; the indefatigable instinct to automatically consider the worst possible outcome whenever we’re deciding whether to let our children ride their bikes down the street or [insert activity here]; the impulse we have to learn ALL THE DATA about every miniscule parenting decision we face; the random bursts of panic and love that are utterly overpowering. (You know what I’m talking about, right??)

- Micromanaging — aka the “alpha parenting nerves” that drive us to (over)control how our children behave, speak, play, learn, and generally exist in the world.

These two strains are *very different; they emanate from different places, present almost as separate predicaments, and demand different “solutions” (if you agree that they need solving…).

*We’re working on building some content to address coping with the former — that Real Fear that keeps us up, worrying, at night, or causes us to hold our breath when our children fall/cry/cough/etc, but this article is explicitly focused on the latter. When we talk about “backing off intensive parenting” in this piece, we’re really honing in on the micromanaging side of intensive parenting. Just a heads up.

Parenting intensely is not easy — and in fact, it’s not universally accessible. It demands time, resources, connections, knowhow. A certain worldview, a certain willingness.

“Not only was the job of parenting smaller before the advent of hovering, but it was spread out over more people.”

~ Salon.com

But now this style of parenting has become the paragon: recent research out of Cornell University that analyzed surveys from more than 3600 parents reported that “the majority of [American] parents think intensive parenting — a round-the-clock devotion of attention and resources to children’s free time, emotions and behaviors — is the ideal way to raise children, even if they lack the time or finances to do so.”

“The new trappings of intensive parenting are largely fixtures of white, upper-middle-class American culture, but researchers say the expectations have permeated all corners of society, whether or not parents can achieve them.”

~ The New York Times

There is a growing segment of American parents, though — and I’d like to count myself among them — who are eager to push back against this ideal and “quit” intensive parenting. To change the norms.

There are lots of reasons to want to do so. Elliot Haspel summed it up nicely in The Atlantic: “rafts of research prove that intensive parenting mainly serves to burn out parents while harming children’s competence and mental health.”

So what if — like me — you want to quit? Or maybe you just want to preempt it from happening in the first place? How do we start?

A quick note: We believe it’s important to point out that our treatment of the problem, as it were, of intensive parenting, stems from a place of privilege and even bias. The fact that we, as parents of young children, find ourselves in the position of asking ourselves this question — how do we stop micromanaging our children’s lives? — belies the reality of our various situations. In other words, we recognize that we’re fortunate to be in the position of wanting to ease off.

So many families don’t have the time or resources to practice intensive parenting — much less contemplate its faults — and we think it’s important to acknowledge that. Likewise, some of the strategies we outline here are going to be more or less accessible depending on your family’s income and socioeconomic background, the availability of child care, your family structure, and where you live, among other considerations.

These inequalities — in and of themselves — are just one of the many reasons we think it’s worth our collective efforts to shrink back where we can.

Nine Ways To Be a Good Enough Parent

You may have read about various parenting styles or decision-making tools aimed at giving children independence. But too often, we focus on the dramatic examples of such “loosening up” (i.e., Lenore Skenazy’s now-infamous story about letting her 9-year-old son ride the NYC subway home; various media accounts of young children going out into the world — the store, around the block, over to the next neighborhood — All By Themselves).

Personally, I think these anecdotes might come at the expense of our attention to the small, everyday decisions we can make that favor treating our children with trust, autonomy, and freedom.

In other words, quitting intensive parenting doesn’t need to be a bonfire.

We’ve put together a list of nine *achievable things you can start doing (today!) to begin to move the needle off “intensive parenting.” Some may feel like baby steps and others like leaps — and not everyone will agree on which is which. But they’re all aimed at the same ultimate goal: giving our kids independence and autonomy to the extent that we can.

As Gail Cornwall quips in a Salon piece on this topic, “my style [of parenting], which revolves around limiting kids’ independence only to the extent necessary to protect them from risks that are both serious and fairly likely to materialize, is now known as ‘free-range parenting’ in the United States, despite the fact that much of the world — including the majority in countries like Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, France, and Israel — just calls it ‘parenting.’”

David Palmiter, a professor of psychology at Marywood University in Pennsylvania, told a reporter for the Washington Post that families looking to pump the breaks on intensive parenting should “focus on two things to build children’s self-esteem: competence and worthiness.”

Everything we included on this list is meant to serve this exact purpose, and help your children feel competent and worthy. If you’re inclined, give some of them a try and let us know what you think!

1. Let your child experience frustration, disappointment, and failure.

This can be surprisingly hard — and it might even seem counterintuitive (how does allowing children to fail help them build competence??), but it’s actually a crucial strategy for teaching children that they are capable.

When we jump in right away to fix something or solve a problem, we’re depriving our kids of the chance to learn to respond in a positive way. Children who experience setbacks or disappointment have the opportunity to learn that these can be moments of growth, and that failure is not synonymous with inability or worthlessness.

Likewise, if children never mess up, feel frustrated or experience disappointment, they never learn to cope with these inevitable situations in healthy, constructive ways. Better to send them out into the world with some tools and practice, experts say, than to shield them from disappointments altogether.

If this makes your skin crawl, start small. Especially for young children, small frustrations crop up A LOT (i.e.: no cookies for breakfast, no chocolate pudding for lunch, no Oreos for dinner, no movie after daycare, it’s raining, it’s not raining, it’s dark, it’s too bright… etc.). Instead of pouncing on every “problem” that arises, try stepping back, acknowledging your child’s feelings and letting them sit with it for a minute. Working through these moments can be a challenge — it takes patience and time — but see how it goes, and build your way up together.

2. Don’t play with your child.

Although the dogma of intensive parenting teaches us that we need to be with our children — engaging with them — all the time, we really don’t. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t spend time with your child, or play with them — have at it, of course! — but rather that we needn’t feel the pressure to do so all the time.

Independent play is super important for young children — it truly is a skill. Numerous child development experts and psychologists have expounded on the myriad benefits of independent play, noting that when adults step in, children lose the reins, as a rule. Even if it’s not our intention, we become the “experts” and the “deciders” simply by our mere presence. Since play is a child’s method of learning, our joining in takes something away from that experience and creative freedom.

Play is also the centerpiece of some educational traditions, such as Waldorf schools. According to Waldorf philosophy, play is children’s “work,” and everything from the classrooms to daily routines to teaching methodologies are founded upon that principle.

If you want a permission slip to “say no,” check out Janet Lansbury’s podcast on this exact topic: It’s Really OK to Say No to Playing With Your Child.

3. Embrace mediocrity.

We tend to be in the habit of doing things “all the way” in this country, and this extends to our children’s participation in activities.

Most of us think, at least on some level, that if we sign our child up for something — soccer, say — their skills and participation will naturally evolve. Maybe you start with a once-per-week low-key toddler exploration program, but over time we expect to see our children improve, probably even excel. And we up the ante, moving from level to level. Up the ladder. This “natural” progression inevitably comes with (much) greater time commitments, higher costs, and a certain serious outlook.

For example, many American parents pursue (their children playing) sports — cough, soccer, again — with a vehemence that borders on comedic. We’ve all seen the soccer coach and soccer mom memes… and if you’ve ever seen a kids’ soccer game, you know that these stem from reality.

Some of you may have also witnessed “those parents” who literally instruct their children through every move at soccer/tennis/tee ball, etc. You’d think every match and scrimmage were the Olympic trials, sheesh! I KNOW some of you will disagree with me… but try backing off at sporting events and see how it feels — I’ve never met a parent who wished in retrospect that they’d yelled louder from the sidelines.

What if we took an entirely different approach — one where we let go of our expectations that our children work to be best in everything they do? What if we were more accepting of partaking in activities without all the expectations and baggage? For — dare we say — fun? Or, what if we simply dialed down the intensity a notch (maybe a few notches)?

We may like to think otherwise, but our kids feel the pressure to succeed, and they internalize it (raise your hand if you remember feeling like you had to “do great” at anything when you were a child 🙋🏻♀️) — often to their own detriment.

How freeing would it be… if we backed off and gave our kids space to figure out what they enjoy doing—not what we think they should do, or what their friends are doing? If we stopped overscheduling them? If we let “good” be good enough and didn’t rush to hire tutors and private coaches at the first hint of interest or glimmer of talent?

~ Julie Suratt, Boston Magazine

In many ways, our collective drive to help our kids succeed is more about us than it is them. For many of us, the prospect of our kids dabbling in activities — without ever really committing to them — seems almost ludicrous. (Why play hockey if we’re not going to DO hockey?) That’s because it’s hard to separate our parenting from our kids’ achievements (or lack thereof)… but these are not the same. I love how Caroline Bologna described it in Huffpost: “One of the best ways to help a child build his or her sense of self-esteem is to separate your own self-worth as a parent from your children’s accomplishments.”

If this^^ is a struggle for you (🙋🏻♀️), you may want to check out Shefali Tsabary’s book The Conscious Parent — it’s kind of life-changing.

A Word on Schoolwork

Extra-curricular activities aren’t the only place where we have the chance to let our children be themselves, mediocre and all (hah). As our growing children come home with school assignments, it can be difficult to avoid hovering, checking, fixing, correcting. But completing such assignments for them — or “helping” to the point of “doing” — doesn’t do anyone any favors.

In fact, when we “help” (read: do) our children’s schoolwork for them, we’re again robbing them of the chance to complete a project on their own, an accomplishment that would deepen their sense of both worthiness and competence. Or we’re depriving them of the freedom to fail at something and then figure out how to overcome it. And we’re also teaching them that they need us to help/supervise/check/correct their work. Those lessons don’t fade quickly…

My son had his first school project this past year (it was a simple, low-stakes, open-ended assignment), and it took not a small amount of self control for me to let him do the project on his own. I wanted to micromanage and make suggestions and help, because I wanted it to look pretty and orderly… But I bit my tongue — because all I could think was, if I step in now, this first time, what happens next? Honestly, I don’t imagine it will get any easier to step away… but I’m banking on repetition building the habit.

4. Sit tight on the playground.

I love the anecdote from Bringing Up Bebe in which Pamela Druckerman contrasts her experience bringing her daughter to the playground in France vs. in America.

In the U.S., we parents climb all over the equipment with our children, play peek-a-boo, and cast sideways glances at the slacker parents who merely follow their children around from the ground (gasp!). In France, parents sit on a bench and read or chat and would no sooner go down the slide or cheer along as their child travails a wobbly bridge than they would break out in song and dance. (Sighs wistfully.)

Our kids don’t need us to narrate their every move at the playground, and it’s okay, really, to disengage with them there. Playgrounds are wonderful places for children to have freedom to explore their physical capabilities (and limitations!), and also to potentially meet and interact with other children. Try sitting to the side for a few minutes, and see how it goes.

Or you can be like these Brooklynites who took it to the next level and started a kids’ “fight club” at the local playground. 😂 I love it.

5. Choose Activities Mindfully

Everyone has a different take on what makes for a great schedule. For some, the ideal day is filled with various forms of formal enrichment; for others, it’s a blank canvas; and for others still the sweet spot lies somewhere in between. Personally, I lean toward the less-is-more philosophy here, but I love having *some* after-school weekday activities to frame our week.

Whatever you prefer, it’s incredibly helpful to devise some sort of framework for deciding whether or not to do X.

First, think about your own preferences (aka, where do you like to fall on the spectrum from busy to not-busy) and acknowledging what you’d like your family’s schedule to look like. Then, come up with a system for choosing what/whether to get involved with an activity — having an actual predetermined process here will save you the stress of making these decisions in the moment. Because that’s when we really start to lean on external factors (i.e., everyone else’s kids are doing this; or, I feel bad saying no (don’t!); or, I did this when I was a kid so of course my kid will too…) in making choices.

There are numerous ways to do this — you could pick to focus on time, convenience, seasonality, etc. Here are some examples:

- I know some families who have a “one activity at a time, per child” rule.

- A friend will sign up for almost anything on weekday afternoons, but weekends are out.

- One mom has a “20 min” rule — everything that’s farther than a 20 minute commute is out.

- Some families have a “body/brain” sort of scheme, where every child can be involved in one physical activity (sports) and one more mental/intellectual/creative pursuit (music, art, etc.) at the same time.

On a related note, it is also helpful to only commit to activities that really enrich your family’s life. What would our communities look like, if we all took part only in the things that we and our children really and truly enjoyed?

Here are a few further questions you may choose to consider to help you devise a framework for culling your calendar:

- Does your child want to participate? Are they excited and animated, or are you going to have to cajole them into partaking?

- Does the activity streamline your schedule or is it logistically challenging?

- Is it age-appropriate and/or developmentally suited to your child? (Is your child likely to be able to wait for her turn, if that’s required, or follow along reasonably well?)

- Why are you signing up? What do you, as a family, hope to gain from participating?

For a laugh: one dad’s testimony about his child’s empty schedule:

“My oldest, age 9, still doesn’t play any sports (by her own choice), which is enough to get me locked up for neglect in some parts of the country. But she recently joined a robotics club she thought sounded fun, and she likes it so far. Maybe she’ll stick with it and turn it into a lifelong pursuit. Maybe she’ll drop it next year to focus on choir, or join a running club, or stand around our yard and poke things with a stick. I’m letting her explore her own interests because that’s what’s best for her. The fact that it lets me be lazy and not fly around the country for sports competitions is just a bonus.”

By the way, some you may be wondering — how will my child ever know she’s interested in clay-making/gymnastics/the drums/basketball/voice lessons/glassblowing if she doesn’t try them all? We thought about this, too, and we like the expert opinion that ideally, our kids should be BEGGING us to try something before we sign them up. So many young children have *fleeting interests — they often are intense, so we run with them, but they typically pass by as quickly as they arose…

While we’re on it, can we just say that it’s hard to make these kinds of decisions in isolation? It’s a challenge to let your child do their own school work if everyone else is coming in with professional-grade work. It’s hard to relinquish control when we’re in a hurry. And it can be very difficult to choose just one or two (or, gasp, no) activities if everyone around you is signed up for umpteen things at any given time. There’s a certain brand of parenting FOMO at work here…

This is where we think it’s so helpful to think about the long game. As parents, we spend a lot (most?) of our time focused on the here-and-now: getting dressed, getting out the door, eating a meal, bedtime… It’s the minutiae in which we are swamped, and it’s the minutiae on which we dwell. And in the morass, it can be hard to remember why we’re making certain decisions — it’s all too easy to forget our resolve.

But zooming out can be a powerful reminder and motivator. Just like with discipline or expecting your children to contribute to the work of the household (see below), choices that may feel costly in the moment in fact have the potential to reep long-term benefits. Making the choice to quit intensive parenting (or try to, hah!) is about raising children who grow up to be independent, capable, confident contributors to society. It’s about raising children who can go out into the world on their own, navigate new situations, and learn in the wild.

To a certain extent, to reject intensive parenting is to make a philosophical commitment to your child’s self-sufficiency — and depending on your perspective, that may be either beautiful or terrifying (or both).

6. Let boredom happen.

Boredom is having a renaissance moment (I think) as more psychologists, scientists and researchers are documenting the creative benefits that come hand-in-hand with boredom — for both children and adults. (See, for example, Jenny Odell’s popular book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy and Manous Zomorodi’s book Bored and Brilliant: How Spacing Out Can Unlock Your Most Productive and Creative Self.)

Boredom can be an important launching pad — the unstructured time and space that leads children to whine that they are bored is an opportunity. Children who work to overcome feelings of boredom are effectively expanding their creativity, generating ideas, and developing skills (such as problem-solving, planning strategies, or communication)… and they usually come out the other side feeling proud of themselves.

Another benefit: children who can sit and/or cope with boredom are also learning patience. They are probably going to have a better capacity for things like waiting in line, waiting to speak with you, waiting their turn, or sitting through something they’d rather not (a sibling’s recital, say) than a child who expects to be stimulated at the slightest indication of boredom. [See also: Reconsidering Screen Time: Research, Reason, and Real Life.]

The point is: if your child is bored, let them be bored. I’ve been amazed at the ridiculous things my kids have come up with when they’ve had nothing better to do — and I’m sure you have too. It’s a beautiful thing.

“If I had one message for a parent it would be this: don’t be scared of boredom. Let it into your life and your child’s life too.”

~ Dr. Sandi Mann, author of The Science of Boredom, @theBBC

7. Welcome your child’s help.

We may think that offering autonomy needs to be some dramatic gesture or solo venture, but it really doesn’t. Indeed, one of the most common ways children seek independence is at home, right under our noses: when they ask if they can help.

Try this at home: Count how many times in a day your child asks to help, and tally up how often you say yes vs. how often you refuse.

Depending on the exact circumstances, this question from a child — “can I help?” — can be either one of the most endearing or one of the most trying questions to respond to as a parent. The reality, as I’m sure you already know, is that young children’s “help” often manifests as just the opposite — everything takes three times as long (at least), may or may not involve a complete reset or something breaking/spilling/getting lost/etc., and the end result usually needs a touch up to boot. Most of the time, we don’t feel like we have the time to let our children in.

But every time we say “no,” “not right now,” “maybe later,” or “I’m just going to do this by myself,” not only are we teaching our kids that their contributions aren’t important (a lesson which typically leads to their not wanting to help later on), but we’re also conveying that they aren’t capable.

As a grade-A control freak who gets huffy when messes, spills and the like happen, I’m running late, or things just don’t go as planned, I personally find this precept — to let my kids help as much as I possibly can — to be simultaneously the most approachable to implement but also the most… cringeworthy. Yet every time I say “yes” and watch along as my kids perform some task (make their own snack, fold the towels, stir the pasta, feed the dogs) on their own, I’m amazed to see how happy and fulfilled they are. Seriously, it’s like Santa Claus just walked in.

There’s no *easy way to train ourselves out of our bad habits (turning down our kids’ requests to participate and contribute), but with patience and time it can be done. (Actually, we have a whole series dedicated to letting kids help — it’s subtly entitled “Stop Doing Everything for Your Kids,” lol.) Here are a few pointers that I and my team have found helpful:

- I did keep tally of my kids’ requests to help and my own answers for a week — it was really (sadly) humbling to see how often they asked to pitch in and I turned them down. This was a big motivator for changing the ratio to something that wasn’t so… meh.

- Say yes as much as you can — and if someone spills, for example, that’s another teaching moment. Maybe your child learns that they really might need some help pouring the full gallon of milk (or maybe you watch along in astonishment as your 3-year-old somehow manages it, hah!). Or maybe they spill the milk… perhaps it’s annoying, but it’s also just another problem your child can feel good about helping solve. It’s amazing how quickly children learn these scripts. After a single spill, my daughter picked up what she needed to do the next time it happened.

- Reframe a no — instead of saying no, find something your child can do to help. If you’re in a huge hurry and you really don’t have time for your child to pitch in, can you find one small piece of the task she can help with? Similarly, if you are uncomfortable having your child help with something for safety reasons (chopping vegetables, say), see if you can’t find a way to include her in baby steps. (Hey, the Bezos did it! LOL) Perhaps she can watch along, or cut a few slices with you, wash the vegetables, place them on a plate, or chop something soft with a dull knife — anything. Many of the tasks we worry about our children helping with can be broken down into manageable steps. Work your way up.

- Start earlier than you would — since children’s help inevitably adds TIME, plan for more. Consider starting dinner 10-15 minutes early, or planning extra time at the grocery store, or for unloading the dishwasher to be an actual bona fide activity. When we build in extra time for the things we need to do, we’re accounting for the delay that comes with our children’s help, and don’t need to fuss about it.

Again, for more advice on letting your children help, see Practical Ways to Include Kids in Household Upkeep.

8. Check yourself: stay out of it.

After I read Michaeleen Doucleff’s book Hunt, Gather, Parent last year, I started to pay attention to how often I intervened on something my children were doing/saying/thinking, and it was mildly horrifying to recognize just how often I was in truth bossing them around.

I realized I was telling them what to say, how to act, or how to do something SO MANY TIMES throughout the day. Not to mention all the times I corrected them or took over something they were working on (turning their jacket “right side out,” making their bed, filling up their water bottles…) with no explanation other than, “just stop, stop! I’ll do this.”

Every single one of these instances was the equivalent of me shutting down my kids’ independent initiative. It’s like when my husband is loading the dishwasher and I take over and tell him he’s “doing it the wrong way.” I know I shouldn’t, but it’s so hard to stop myself.

Psychologist Peter Gray has written extensively about the value of letting our children be as much as we possibly can — letting them choose what to say (or not) and when, how to play and work through disagreements with other children, forget things or do things “wrong,” or just work on something in their own way. Gray’s preferred parenting style is called “trustful parenting,” and he describes it like this: “Trustful parents do not measure or try to guide children’s development, because they trust children to guide their own development. They support, rather than guide development, by helping children achieve their own goals when such help is requested and needed.”

Intensive parenting is almost entirely bereft of the kind of trust Gray describes (it’s by nature directive and protective, Gray says), and our kids are missing out.

It’s hard to step back — it really is — but give it a try, see what happens. When my husband and I decided to make a concerted effort to NOT intervene or direct our children in any way (a commandment we both *struggle to follow), we watched in stunned awe as our kids brought tasks to completion, figured something out, or navigated disagreements on their own.

It’s never perfect — sometimes it’s a huge mess, actually, and there are times where I’m left feeling embarrassed about something they said/did (or didn’t say/do). But more often than not, they rise to the occasion. Who knew. And however it works out, their sense of achievement is visible every time.

This is where the idea of benign or loving neglect comes into play — and once again, our stepping back and out of our kids’ way is so much more about US than it is them. Jessica Lahey wrote in her book The Gift of Failure about her own struggle to stop doing things for her kids: “I had to stop equating the act of doing things for my children… with good parenting,” she said.

This SO resonates with me. I feel like I’m being irresponsible if I leave my kids fighting over something, or worry about what kind of mother I look like if I don’t make them apologize to a friend, for example, or pack something I’ve already reminded them they need to bring in to school, but the philosophy of trustful parenting teaches us that our kids will learn these things on their own in the long run… if we give them the chance.

9. Ask your child: what do you want to do?

Last but not least, I encourage you to ask your child if there’s something they’d like to do on their own. You might be surprised to hear what they say — and maybe it will even be well within reason. (When I asked my kids, one said “make my own snack after school” and the other said “push the button to open the garage door when we leave in the morning.” Done and done.) Maybe they’ll ask about something you’re less comfortable with, but even so, perhaps there’s a way to break things down, or explain that you can do it together until they show you they’re ready on their own.

I’ve been asking my children this question (is there anything you’d like to do by yourself?) periodically, and I’ve also been trying to observe more closely what my children seem eager to do on their own. Wherever I can, I’m doing my best to invite them to try new things without my help/oversight (go into the changing room by themselves to change after a swim lesson, or pick avocados at the grocery store, for example). It’s incredible to see how much these moments really matter to them, and how much they relish whatever snippets of independence they have.

As an added benefit, I feel less bad about the moments when I do insist on partaking/helping — because those are still many and varied.

If you’d rather not leave this^ open-ended, here are some ideas for things kids love to do by themselves:

- Feed the pet

- Check the mail

- Cut food

- Water plants

- Climb in/out of the car seat by themselves

- Pour things (anything, LOL)

- Cross the street without holding hands

- Play outside

I took for granted that my kids were fighting for independence when they were toddlers, yes — but I wasn’t ready for the fact that their desire to do things on their own only grew from there. Exponentially.

It’s hard, but I’m realizing that I need to make more of an effort to meet them halfway.

Doing this requires, more than anything, that I get out of my own way. Because the more I pay attention, the more I am mindful of all the ways in which I am intensively parenting, the more I realize that everything I think I am/need to/should be doing for my kids has so much more to do with me — my own stresses, fears, idiosyncrasies, and time management issues — than it does my kids.

“If you want responsible kids, you have to give them the freedom to be responsible.”

~ Peter Gray, Free to Learn

And while disengaging from the dominant parenting paradigm in America today (that of intensive parenting) is no small task, I’ve found it comforting to witness that we can push back, in so many little ways, that don’t require us to change schools, move to the homestead, or deny the reality of our anxieties. Instead, these little opportunities ask us to take a deep breath, protect our unscheduled time, and believe in our kids. And at the end of the day, I’ve never regretted that.

Great article Brittany! Lots of fantastic links and practical actionable information!

I love this article. My only question is – doesn’t homework sometimes require teaching? I was a kid that never needed help with homework, but my little brother definitely needed help with math. I also remember some pretty cute bonding moments when my dad helped him create rhymes to remember things like the state counties. With the issues in our education system (e.g. some kids getting left behind due to lack of resources), don’t parents play a role in complementing the education they receive in class? (Note: I’m aware it’s a huge privilege to have the time to help with homework). There’s a difference between making your kids diorama for them and teaching them a concept they seem to be struggling with. Is there nuance to your “hands off” approach with school, or does the literature say it’s cut and dry – never assist/teach?

Hi Jessica! There’s a big difference in helping a kid understand concepts they are struggling with, etc., and doing things for them (or doing a project for them, for example). I know parents who DO their kids IXL math work because they are simply tired of battling their kids on it (too much homework is a whole other issue).

So it’s helping them learn how to arrive at the answer vs. giving them the answer in order to “check it off the list”.

Cheers!

This is really REALLY helpful and eye-opening. Question (for a friend) about the soccer/playground scene: what about the kids who are shy or fearful and are BEGGING for you to go with them on the field (or you are the one begging them to go out there as they cling for dear life to your arm)? Do I (sorry, they) still just sit on the bench and painfully wait even if nothing happens? I realize this more about the parent and not the five year old – so no need to skirt whatever you’ve got to say. Thanks!

Hi Meagan! LOL – you make me laugh.

I would tell your friend that — for the kid who is too shy to get off the bench — they should watch and wait until *they* decide they want to go in and play. Once they get some level of comfort with it, they will let you know. And if they have no interest in playing… then there’s your answer (and not always the one we want to hear, unfortunately).

Thanks for reading 🙂

Wow, such an insightful, well thought out piece. So much for us to think about and evolve towards as parents of young kids.. no pressure!

This article was really insightful to read! Thank you!

So many things to think about here! I really appreciate the balance of theory and practice throughout the article. And thank you for being vulnerable yourself. That’s tough as a mom in this day and age.

This article is GOLD. Loved all the links & book recs too. Thank you much for using your platform to address this.

I loved this article and I love all your content in general. It’s so real and relatable and written in such an inviting and approachable way. Thank you!!!

What a great read! Lots of good nuggets to come back to! Thank you for sharing—so many things resonated w me.

Thank you so much for this. It consolidates so many things I’ve learned and struggled with as a parent. It’s been such a relief to release some of the burdens I carried early on about doing everything for/with my kids. I love the book recs too, I added several to my list. Other books that support this approach that I’ve found really helpful are “Simplicity Parenting” by Kim John Payne and Lisa M. Ross and “How to be a Happier Parent” by KJ Dell’Antonia.

Very well written, per usual! I subscribe to a lot o these parent philosophies, and I am often the “black sheep” of my mom friends (in a loving way, of course!). So I am glad to see more advocation for less scheduling, less hovering, and more focus on raising good people

Raising children is hard work! thanks for this article!

This is incredibly insightful and useful. Thank You

This article on “Good Enough Parenting” is such a refreshing read! It emphasizes the importance of not striving for perfection as a parent, which can relieve many of us who often feel overwhelmed by societal pressures. Your perspective on being “good enough” resonates with me, as it allows for flexibility and acknowledges that we are only human. Parenting is a journey, and it’s great to see an article that encourages self-compassion and acceptance in the face of the inevitable challenges we encounter. Kudos to you for tackling this topic!

Your perspective on parenting during the pandemic is so relatable. It’s interesting how our views can shift when circumstances change. Sometimes, hitting the pause button and reevaluating our priorities can lead to unexpected insights and a newfound appreciation for the simpler moments with our little ones. 💕