Pain Relief for Labor and Delivery

You may or may not have heard that labor can be… painful (humph). Spoiler alert: it is. Yes, there are some women who would disagree with me, but by and large I think most of us would safely agree that pain is part of the process.

The good news is that you have options. (Also: you’ll have a BABY at the end of it! Holy smokes!)

*Note that this article covers pain relief options for labor and vaginal deliveries (i.e., not C-section anesthesia).

This piece is going to give a *broad strokes overview of pain relief options that may be available to you during labor and birth, both pharmacological and otherwise. We’re going to spell out the basics, but as always, please talk to your doctor or midwife for specifics and for particulars relevant to your body and pregnancy.

On Pain

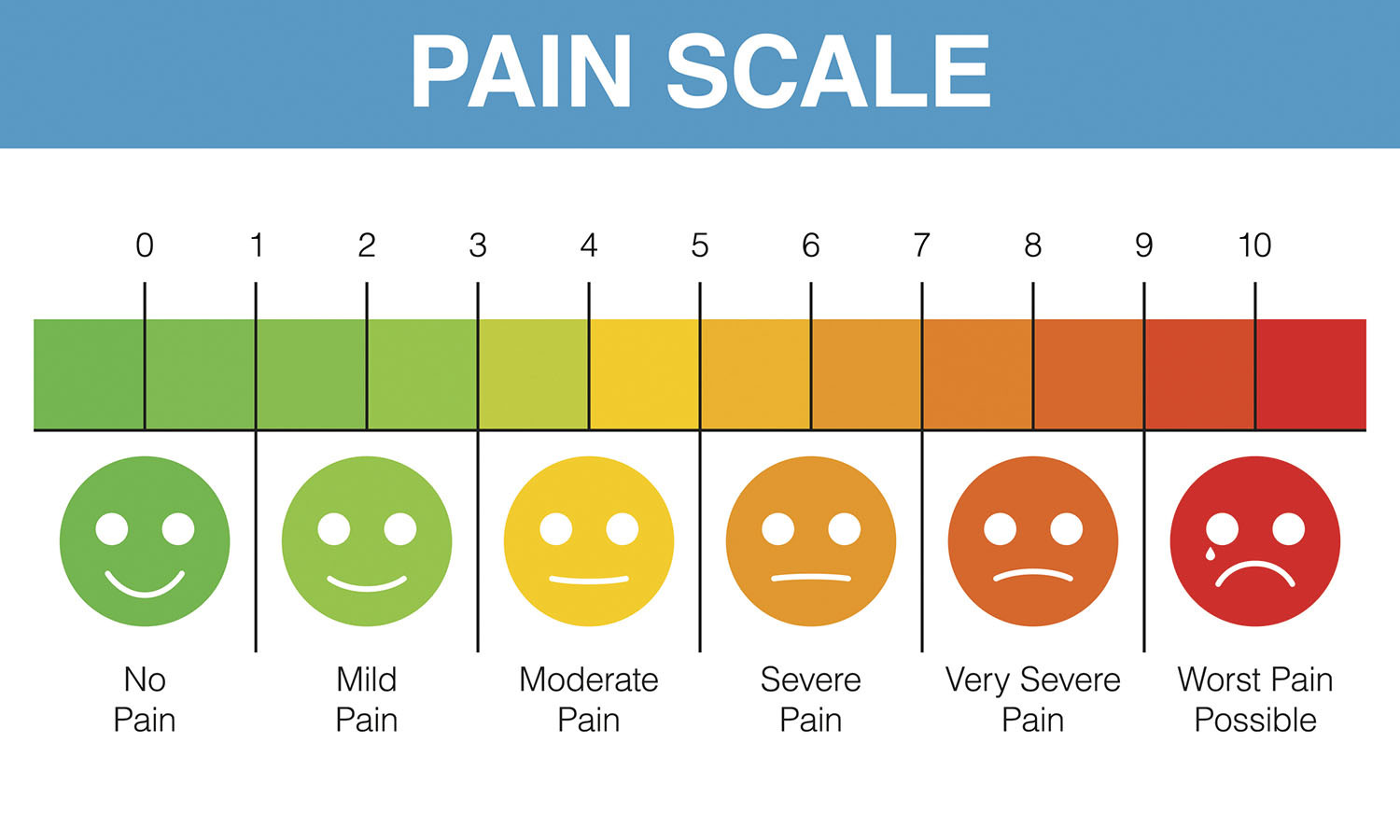

Before we begin, let’s take a minute to acknowledge that pain is a very personal thing. In fact, pain is one of the most highly subjective phenomena in the realm of “medicine/health/wellbeing.”

The experience of pain is the result of a super complex web of interactions and is mediated by all kinds of different factors: your body, your past and personal medical history, your environment/setting, social context, psychological influences, and culture (to name a few). Researchers also know that expectations can play a role in the experience of pain. So can anxiety and fear. So too can self-confidence.

In many ways, we might say that pain exists in the mind of the beholder (so to speak). Every person’s perception of pain at any given moment is always going to be unique, and it’s important to know this at the outset.

Labor pain is unpredictable, variable, and particularized. It’s well established yet singular, collective yet individual.

“The experience of labor pain is a highly individual reflection of variable stimuli uniquely received and interpreted through an individual woman’s emotional, motivational, cognitive, social, and cultural circumstances.”

— Executive Summary on the Nature and Management of Labor Pain, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Birth plans are, frankly, over-politicized in this country (just my take) — and they really shouldn’t be. In my book Carrying On, I explain that having (or not having) a birth plan is neither implicitly “good” or “bad.”

Instead, what’s valuable about a birth plan is the process of making it; it’s the actual time and thought that goes into formulating some sort of birth plan — and communicating it — that is most valuable to women (vs. the details of the plan or the plan itself). And many experts rightly suggest thinking about birth “preferences” rather than plans, because it’s completely impossible to predict how you will feel and what will happen.

What you DON’T want to happen is that you devise a birth plan and then wind up feeling like you can’t deviate from it. So flexibility and “what if…” thinking are your friends here, folks. (It’s SO hard, I know…).

This is why it’s so valuable to head into labor knowing what your options and preferences are. Some women who plan to have an epidural STAT assume there’s no need to learn about any non-pharmacological methods of pain relief, then go on to have a labor that moves along like wildfire and there’s just no time for drugs. Shoot. Other women who desire an unmedicated birth may similarly assume that there’s no need to inquire about pharmacological pain relief, then proceed to have a crazy-long labor that stalls in part because they just need to rest. It would have been nice to know about some options, right? Before you’re in the moment.

Wherever you’re standing today, it’s our aim and intention here to introduce the most common pain relief options across the board, so you know what’s what. Talk to your partner. Talk to your doctor. Talk to your midwife. Talk to your doula or your mom or your sister or your friends. Hopefully this gets you started. 🙂

A quick history in the U.S.… (because I can’t help it, this stuff is seriously fascinating).

Before about 1900, labor and birth alike happened at home. For the most part, it was women — not doctors — who attended births. When labor started, neighbors, family and friends who could showed up to help. And many women knew well what they were doing because they’d been there. The average woman gave birth roughly five times over the course of her life, so between personal experience and offering assistance to others, labor and birth were a very regular and familiar part of women’s lives. (Note that this was not all love and joy and sisterhood — maternal mortality at the time was sky high, and women greatly feared the pain and the possibility of complications and death that came along with childbirth. Not to mention that infant mortality rates were also incredibly high.)

Around the turn of the twentieth century, these general circumstances began to shift — gradually, birth became something that demanded formal medical attention. Ultimately, it moved primarily to the hospital setting. By the 1930s, more births took place in hospitals than in homes, and by 1950, some 90% of American babies were born in hospitals. We could talk about the trade-offs that came with this shift — because there turned out to be many — but for now we’ll simply say that women’s desire to access pain relief was a major generator in occasioning it.

You see, before women started showing up at hospitals to have babies, they first invited physicians to attend their births at home — not because they knew how to care for laboring women (physicians pretty much had no clue what they were doing when it came to all things “womanly” [snort]). No, many women first asked doctors to join in because they wanted pain relief.

The doctor’s early arsenal against labor pain (in the late 1800s and early 1900s) included ether and chloroform, both of which essentially knocked you out and also had certain risks (which we could broadly classify as “unknowns,” since there were no studies on how these substances affected labor, mothers, or babies). Nonetheless, chloroform and ether were both used widely.

In the early decades of the 1900s, there was also scopolamine, otherwise known as “twilight sleep,” which exerted frankly terrifying effects on laboring women. Of particular note is that it did nothing to actually relieve women’s pain — instead, it altered their level of consciousness, putting women into an amnesiac, semi-conscious state (hence the name twilight sleep) which left them still fully susceptible to the physical pain of labor and birth, but unable to remember it. Firsthand accounts are truly horrific…

Some scholars argue that the mere presence of male physicians, previously estranged from the entire process, may have actually intensified the experience of labor pain, perhaps by introducing a new source of anxiety or formality (“man in the birthing room!!”). And the changing environment in which birth transpired undoubtedly had the effect of dissociating women from the process.

Since the days of twilight sleep, the pharmacologic menu has both changed and expanded. A modern epidural is not ether is not scopolamine is not an epidural a la 1986, but it’s interesting to contemplate the origins here. Especially because over the course of the 1900s, and in particular since the 1960s/70s, pain relief during childbirth has become a politicized issue (I touch on this at various points in my new book on the history and science of prenatal care, Carrying On — shameless plug…), to the extent that it can be incredibly divisive and polarizing. In my experience, there tends to be a certain amount of… moral judgment.

You won’t find any of that sh*t here.

We believe that every woman has the right to make her own decisions about how to experience and endure labor and birth. And like so many, many, many aspects of motherhood, this is not a black and white issue. If you plan on getting an epidural, that doesn’t mean you can’t also benefit from non-pharmacological methods of pain relief; if you plan to eschew medication entirely, it’s still nice to know what’s available, because you just never know. I love how our friend Jen Mayer, doula, maternity leave planning coach, and founder of Baby Caravan (a fabulous doula collective in NYC), put it: “No matter what your preferences, you will be best prepared to inform yourself for every option… We never know how things will unfold,” she told me. “And the more options we have, the better we will fare.”

Okay, phew. Last thing, real quick, before we get going…

*ASK ABOUT WHAT OPTIONS WILL BE AVAILABLE TO YOU. Labor and delivery pain relief options, policies and procedures can vary GREATLY by location. Some hospital maternity rooms have birth tubs, for example, while others don’t; birth centers may have nitrous oxide, but almost as a rule won’t have epidurals available. Some hospitals have a robust anesthesiology team available at all times; others may only have one. Your choices and experience are, for better or worse, highly dependent on geographic circumstance. (And you may want to ask about costs for different pain relief methods, too — as NPR reported in 2019, charges can vary widely.)

Alright, now, friends. Let’s go — first, the drugs…

The Pharmacology Side of Things

In the pharmacological realm, there are two main overarching categories of pain relief: anesthetics and analgesics. Let’s dive right in, shall we?

1. Anesthetics/Anesthesia

Anesthetics, as a class, provide relief by blocking feelings, including pain. They can be:

- Localized to a particular spot on the body (for our purposes, localized anesthetics are typically employed during labor and delivery for comparatively short-term numbing purposes, such as numbing the perineum with a shot if you’re having an episiotomy), or

- Regional (typically below the waist).

There are three main categories of anesthesia available during labor and delivery: an epidural, a spinal block, and combined spinal-epidural.

Compared to opioids (discussed below), these anesthetics have the advantage of not affecting your consciousness level at all. With all three, you will still be fully awake and aware.

“Systemic medications [ie narcotics, see number 2, below] produce drowsiness and sedation in addition to pain relief while the epidural or spinal medication acts only locally, so you will be comfortable, alert and able to fully participate in the birthing process.”

1. An epidural block (aka “an epidural”)

This is the most common source of pain relief among childbearing women in the US. An epidural is intended to result in some loss of feeling in the lower half of your body. Typically, women who receive an epidural can move their legs around a bit but can’t walk. You should also be aware of contractions — which may feel more like a gentle pressure or a menstrual cramp rather than a walloping labor pain — so you can push when it comes time.

You may have heard of a walking epidural — this is essentially a “toned-down” version of a “regular” epidural (i.e., with lower meds). The idea here is that smaller doses of the medications in an epidural (& or spaced out over more time) allow for some relief but also leave more feeling/sensation intact.

*However, the name is somewhat of a misnomer, because most women who receive so-called walking epidurals are not actually walking around. With a walking epidural, you can move your legs more freely, but still by-and-large aren’t able to reliably pace around. In fact, many hospital locations explicitly prohibit women who have epidurals from standing and walking (for insurance/malpractice purposes). This isn’t universally true, but it’s something to know and ask about, and it’s a reminder that an epidural is not necessarily a one-size-fits-all proposition.

The administration: *Some locations may ask that your partner leave the room for this entire process, FYI (because, YES, some partners faint and then there is another patient to take care of…). First, an anesthesiologist will apply an antiseptic solution to your skin to prevent the risk of infection. Next, they will administer a numbing agent (aka a local anesthetic), which often feels like a pinch and a burn. From that point on in the procedure, you should feel only pressure, not sharp pain. The anesthesiologist will then attempt to insert a needle into the epidural space, which is located above the outermost part/layer of the spinal cord. It’s bordered by the bottom of the skull (at the top) and the sacrum (on the bottom), and it’s considered a “potential space.” The only things it contains are fat, spinal nerves, small blood vessels, and connective tissue (no fluid).

Once the needle is successfully inserted into the epidural space, the anesthesiologist will thread a small tube (a catheter) through the needle and into the space, then remove the needle and secure the catheter in place with a lot of tape so it will stay put throughout labor and delivery. The epidural medications — typically a combination of local anesthetics and opioids — flow through the catheter and into the epidural space to bathe your nerve endings (this is what provides the pain relief).

Since the catheter is the delivery mechanism here, your anesthesiologist will need to take the time to place it carefully and well. They’ll ask you to sit in a sort of hunched-over position (making a shallow C-curve with your spine) or lie on your side; in both cases, you’ll need to stay very still for the procedure. From start to finish, the whole process typically takes about 15-20 minutes, and your provider may ask you for feedback along the way, such as whether you feel pain/pressure on either side of your body, to help ensure the epidural is placed in the optimal location.

Things to know:

- There may be a waiting period before you can get the epidural — if and when you decide you want an epidural, you are usually in the position of wanting one RIGHT FUCKING NOW. But the hospital takes time to place these kinds of orders. From the moment you say, “let’s do this,” you may have to wait (sometimes for quite a while) before the anesthesiologist arrives. They may be attending to trauma or surgical patients that take precedence over you. And then…

- An epidural takes a little while to kick in (~15-20 minutes) — and you may be thinking that this doesn’t seem like all that long, but in the world of labor, 20 minutes can feel like seven hours… Hence, again, we urge that, even if you plan on getting an epidural, you continue reading to learn about other methods that can help you bridge the gap. (Or, you could also consider asking for an epidural preemptively — more on this in a moment.)

- Epidurals can be set-up to deliver medication continuously, intermittently, or both — many are continuous but also have patient-operated triggers that can deliver a quick bolus of meds when you decide you need it (you just press the button…). (It’s regulated such that you can’t overdo it.)

- You can actually talk to your health providers about the level of meds you want and/or how quickly you’d like it to wear off — yes, you can! Remember what we said about walking epidurals? You can discuss the level of medication/relief you desire (they can adjust the rate of delivery) — and remember that if you don’t “like” the epidural, you can always ask for it to be turned down or removed. Feeling won’t return immediately, but it will come back.

- A good epidural should not make you completely numb — the point of an epidural is NOT to take away all pain, but rather to help control your pain. You still want to be able to feel a certain amount of pressure so that you can actually know when to push. IOW, you want to still be able to feel your legs and feel pressure. **And if you can’t move your legs at all, it may be a sign the catheter is not in the correct location or that your rate of medication delivery is “too high” — if you are concerned, ASK to speak with the anesthesiologist on the L&D floor.

- Because of the time it takes to set in place and actually begin working, you can’t get an epidural if you’re too close to delivering (there’s no sure number here in terms of what constitutes “too close” — it’s going to depend on how much you’re dilated/effaced, where the baby is, the anesthesiologist’s availability, and your doctor’s take on things).

- Getting an epidural may wind up feeling like there’s a lot of… additional medical interventions. It’s helpful to know what to expect, and when you add everything up, some might say that an epidural comes hand-in-hand with a lot of equipment/medical tech. You’ll have an IV fluid bag (thus, you’re hooked up to an IV); continuous fetal monitoring; a catheter for urine (remember, you can’t get up to use the bathroom); maybe a pulse oximeter on your finger. As Jen described it to me, “it’s fine, a lot of people do it,” but if you don’t know about it, all of this can feel a bit overwhelming. Now you know.

- You may have to stay in bed for a period of time even after you deliver — recall that most hospitals won’t permit women who have epidurals to stand up or walk around. Even after you’ve delivered and the epidural catheter is removed, your OB team may still expect you to stay in bed for a brief period of time to ensure you have full mobility of your legs back.

- There may be eating and/or drinking restrictions while you are on an epidural — this varies by location, and you can ask ahead, but most hospitals have some sort of dietary restrictions for women on epidurals (i.e., you can only consume small sips of water or suck on ice chips; you can only have clear fluids, etc.).

- Depending on your hospital, your epidural may be placed by a resident or fellow physician (i.e., a physician completing training in anesthesiology), a CRNA (a nurse anesthetist) or an AA (anesthesia assistant, similar to a physician assistant). It’s not only anesthesiologists who are trained to perform epidurals.

- Your birth is not “less than” if you have an epidural! I loved what Jen told me on this one, too — “an epidural may take away the hard edges of labor pain, but you still have to labor and you still have to push a baby out, and that’s pretty badass!” 💪

- Dr. Shana Dowell, Associate Professor of OB/GYN at Vanderbilt University, told me that even though some people would disagree with her, she thinks there is no reason women need to “wait” to have an epidural — even if you’re in very early labor, she said, you could have one if you wanted to. In fact, you will likely be asked if you want one when they know the anesthesiologist is available. This is typically to preclude you from getting stuck in the aforementioned waiting line…

The Benefits of Getting An Epidural Earlier

Dr. Erin Zenilman, an anesthesiologist and mom of 2, recommended that women who know they want an epidural consider requesting one sooner rather than later — even if you’re not yet in pain. (Most OBs and anesthesiologists will agree to do so.) Here’s why:

- As mentioned earlier, L&D floors are very unpredictable — and if things are super busy and/or there are any staffing issues (maybe it’s the middle of the night and only one anesthesiologist is on call, say), you could potentially have a long wait time.

- There’s no harm — if you know you want an epidural, you can request a lower delivery rate of the medication or even no medication early on, and make adjustments as labor progresses, but this is one thing that’s “done.”

- If you have questions to ask the anesthesiologist, it’s much easier to have a calm, clear, informative conversation when you’re not in pain (i.e., before active labor really gets going). Alternatively, if there’s anything you need to tell the anesthesiologist — such as a scoliosis diagnosis or any other relevant piece of your medical history that might make epidural placement more challenging — you’re more likely to remember to tell them.

- It’s much easier to sit very still for the epidural placement before contractions really pick up.

- Lastly, in the RARE event that you have to have an emergency C-section, your team will be able to administer regional anesthesia quickly. (Vs. if you don’t have an epidural in place and there isn’t time for a spinal, you may have to undergo general anesthesia.)

There’s a segment of people who think that they’ve somehow failed if they get an epidural — but this is a terrible way to feel about the entire experience! You wouldn’t go to the dentist to have a tooth pulled and reject pain meds… the notion that “it takes a real woman to have an unmedicated birth” is disempowering.

~Dr. Shana Dowell

2. A spinal block

A spinal is a single injection shot of medication into the spinal fluid around the spinal cord. This delivery goes past the epidural space into the “next layer,” the subarachnoid space, where cerebrospinal fluid bathes the brain and spinal cord; it uses a smaller/thinner needle than an epidural. A spinal block has the effect of relieving pain very quickly (almost immediately), but it is temporary (usually lasting only about an hour or two).

Because they are so temporary, spinals are not super common. As Dr. Braveman explains, “We don’t typically use a single dose of spinal medicine for a vaginal delivery unless we have a good sense that the patient is going to deliver quickly.”

3. A combined spinal-epidural block

The spinal-epidural is the proverbial one-two punch in the world of pain relief: the spinal (#2, above) works to quickly relieve pain in the immediate, and the epidural keeps the pain relief working for the long haul.

The spinal-epidural medications typically combine anesthesia with an opioid analgesic. (Compared to receiving a more concentrated dose of narcotics alone, the amount included in an epidural is smaller and therefore lowers the chances for adverse effects.)

The spinal-epidural is administered through placing a needle in your lower back (as in the epidural), followed by a single spinal shot (administered through the epidural needle); then, a catheter is inserted into the epidural space for the continuous delivery of medications.

Cochrane authors (a systematic review of evidence conducted by objective experts — these are overwhelmingly considered the gold standard for evidence-based decision-making in health care) reported that when comparing a stand-alone epidural to the spinal-epidural combination, there were no perceived differences in patient mobility, labor progress, or cesarean delivery rates. They also noted that women who received combined spinal-epidural anesthesia had “less need for additional or rescue anesthesia interventions, instrumental delivery, and urinary retention” (again, compared to a traditional epidural). So that’s interesting.

*Note that some hospitals do not offer a combined spinal-epidural.

Epidural & Spinal-Epidural Side Effects

There are a handful of severe side effects that are possible (i.e., residual numbness, infection), and your doctor can tell you more about those, but they’re incredibly rare.

Here, let’s simply review the more common side effects (these aren’t “likely,” in the statistical sense, just more prevalent than serious complications):

Here are the more common side effects that are possible:

- A decrease in blood pressure

- Bleeding

- Itching

The meds in an epidural can make you feel itchy, and it can occur anywhere but is short-lived (i.e., it goes away after the medication is out of your system).

- Spinal headache (or postdural puncture headache)

This is probably the most common side effect that can happen with epidurals — and it’s dreadful. A spinal headache can be pretty terrible (think: migraine on steroids) and, untreated, may last for 1-2 weeks. Noninvasive interventions like caffeine and hydration can help, but they don’t solve the underlying “problem,” which is: during the epidural placement, the needle was inserted too far, past the epidural space and into the subarachnoid space, and a small amount of cerebral spinal fluid may have leaked out, altering the balance of pressure between the brain and spinal cord (this is the theory, at least).

In most cases, the anesthesiologist should know if the needle was inserted too deep, because some clear fluid usually leaks out (there shouldn’t be any fluid when an epidural is placed correctly). Most anesthesiologists are trained to inform a patient if this happens, because this is essentially what may put you at risk for developing a spinal headache.

Spinal headaches can be treated with a targeted procedure, though of course that entails a separate intervention that then comes with its own risks (bleeding, infection, back pain, bruising). At the most rudimentary level, the treatment (a blood patch) entails drawing your blood and then basically reinserting it into the epidural space, like a plug. “It really does help women turn the corner,” Dr. Dowell said. The risk for a spinal headache is small (about 1 in 100), but there is emerging research indicating the effects may be “more serious and persistent than previously thought.”

Moving on…

- Local reaction (allergic reaction)

- Backache

Although official studies don’t necessarily indicate as such (data pooled for a 2011 Cochrane review indicated that epidurals did not lead to an increased risk for long-term backache), many women do report having a sore back for quite some time. Back pain can be more common if you have to have a needle placed more than once — but usually recedes within a couple of days.

- Sometimes things don’t work…

Many women report their epidurals not working as intended — it can wear off, only work on one side of the body (a sign the catheter is aimed too far toward one half of the body), the catheter can dislodge, and depending on the location of the baby as labor progresses, there may be a window of time during which you don’t have pain relief… check out our FB poll on this topic for personal testimonies in this arena… and take note of the common “no one believed me” thread (grrr). If this happens to you (🙋🏻♀️), speak up! You have to be your own advocate. (For reference, UNC’s Department of Anesthesiology estimates that relief from an epidural may be “patchy” or “one-sided” in ~5% of patients.)

**By the way, women’s experiences of pain have historically been dismissed, overlooked, or simply not believed. This still holds true today. And women of color are even more likely to be disregarded — including in the delivery room. Indeed, studies show that there are stark racial discrepancies in epidural use and efficacy in this country. As sociologists explain, race influences women’s experiences with epidurals: women of color are more likely to face pressure to accept an epidural; “more likely to experience failure in their pain medication”; and “less likely to have their pain and anxiety taken seriously by doctors.” This situation is unconscionable. We — collectively — need more visibility and awareness of this issue, and sharing stories is a start. Thanks to @kit+me for sharing recently — we also suggest the wonderful Birth Stories in Color podcast and the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, too.

- Sometimes epidurals are too strong…

We mentioned above that you should have some feeling with an epidural — if you are numb or completely unable to move your legs, you should probably ask about slowing the rate or turning down your meds. One risk here is that without any ability to feel pressure from contractions, you won’t know when to push during second-stage labor, or may push too hard and risk tearing.

→ It’s important to keep in mind that an epidural is a technical procedure, and just like any other medical procedure, it’s not always a perfectly uniform operation. Everyone’s anatomy is different, and there are some people who are simply more skilled at placing epidurals than others. Though the vast majority of epidurals go very smoothly, don’t be afraid to ask questions or speak up if something doesn’t feel right.

One woman I interviewed told me that the first anesthesiologist she saw tried to place her epidural three times unsuccessfully. After the third time, she said she wasn’t comfortable with him trying again and asked if someone else was available. It wasn’t easy, she said, but she’s glad she did it.

Pro Tip: You don’t have the opportunity to pick your anesthesiologist in the same way you select your OB or midwife, but there are still ways to connect with the anesthesia team prior to your labor, if you want to. Here’s how:

Most hospitals have some sort of pre-op clinic staffed by anesthesiologists. Technically, these pre-admission centers are for patients undergoing a surgery, but they also may afford the chance for you to speak with someone in the anesthesia department prior to labor.

If you’re nervous about getting an epidural, or have questions, ask your OB or call your hospital and let them know you want to speak with someone in the anesthesia department. It likely won’t be the same provider you see when you actually go in for delivery, but speaking with someone beforehand can help you gain a better understanding of what will happen and what to expect at your particular hospital.

Epidurals and Interventions

There is a lot of dated and/or misinformation out there about the relationship between epidurals and interventions — and perhaps especially C-sections.

Word on the street used to be that getting an epidural often led to longer labor and/or was the first step in a cascade of interventions that would likely (if not inevitably) lead to a C-section. In the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, research did in fact indicate that this was the case: epidurals were associated with increased C-section rates.

But newer research in the twenty-first century has indicated otherwise. In 2011, a Cochrane review determined that epidurals did not increase the likelihood of having a cesarean delivery. “Although overall there appears to be an increase in assisted vaginal birth [using vacuum or forceps] when women have epidural analgesia,” the authors said, “a post hoc subgroup analysis showed this effect is not seen in recent studies (after 2005), suggesting that modern approaches to epidural analgesia in labor do not affect this outcome.” ACOG’s practice bulletin reiterates this point, saying that none of the pharmacological analgesia options carry any apparently increased risk for a C-section.

[If you want to read a critical assessment of the data, see here for a deeper dive.]

“Randomized trials and systematic reviews including thousands of patients have shown that the initiation of epidural analgesia at any stage during labor does not increase the risk of cesarean delivery.”

However (and as mentioned above), epidurals do increase the risk for assisted vaginal delivery (using vacuum or forceps), and they’re also associated with slightly longer labors (~40 minutes for first-stage and ~14 minutes for second-stage, on average) — but these numbers are not necessarily super alarming. (Nor 100% telling — they’re just averages.) Dr. Dowell told me that there are robust studies showing that epidurals don’t appreciably slow labor down.

Anecdotally, there are as many stories about this^^ as there are babies born in the wake of epidurals… And the effects on labor are equally as diverse. For some women, epidurals do briefly slow contractions. For others, epidurals actually have the opposite effect — by calming the body and enabling women to relax and/or rest, they can actually speed up dilation and help regulate contraction patterns. Unfortunately, we don’t have a magic ball to see what will happen.

On tearing: Recent evidence (see these papers from 2014 and 2018, for example) suggests that epidurals do not increase the risk for tearing.

Ok! Now that we’ve covered the epidural option, here’s a quick look at another option, though one that is not as frequently used:

2. Systemic Analgesics (aka opioids)

Systemic analgesics work through the full body (hence, systemic) to reduce your awareness of pain and ease pain (not eliminate it); they also tend to have calming effects. Doctors explain that these drugs lessen or dampen pain without causing you to lose feeling entirely or lose muscle movement.

Generally speaking, Dr. Dowell told me this class of pain relief is best for women who don’t want to get an epidural; or for women who just want a break. [Examples include Demerol, morphine, fentanyl, Stadol and Nubain, which is the most common medication given in this category.] They are typically administered with a shot or through an IV, but can also be inhaled (as in the case of nitrous oxide, see more on this one below).

These medications can make you feel drowsy or sleepy (one doctor compared it to the feeling of having had a few drinks), and some women experience nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, etc.

Opioids are typically employed earlier in labor, and are almost never used immediately before delivery (as in, roughly an hour preceding) because they can cause sleepiness (more on that in a minute).

As a category, this class of pain relievers is less common. The most notable downsides here are that these substances provide more short-term/temporary relief (for about an hour or two), and that they can/do affect the baby. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) puts it quite bluntly: “All opioids cross the placenta and may have adverse effects for the fetus or newborn.”

Possible side effects include: variable fetal heart rate/pattern, reduced fetal heart rate, neonatal respiratory depression, and neurobehavioral changes. As the Brigham and Women’s Hospital explains on its website: “The baby has the ability to metabolize the medications, but it does so more slowly than the mother… it is unlikely the baby will be affected adversely as a result of [a] small amount of mother’s medication, but it is important to realize that the medication does impact the baby.”

Some other adverse effects, as noted by a Cochrane Review, include nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness. The reviewers also noted, “although there was pain relief during labor, it was poor… and that there was no great difference between the various agents [meaning, types of opioids] studied.”

Also in this category: Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous oxide, colloquially known as “laughing gas,” has been used widely in Europe for decades, and it’s becoming more popular (and more available) in the US. Nitrous is a gas that essentially reduces anxiety and increases feelings of well-being. It’s administered through an oxygen mask (you inhale a mix of 50% nitrous and 50% oxygen through the mask).

There are a number of reasons why many women really love this option. First, it works fast (in “real time,” as they say — you feel relief very soon after inhaling); and it also has a short half-life. In other words, it wears off quickly, without lingering effects. And since you’re the one choosing when to inhale through the mask, it gives you a lot of control. When you need more relief, you can use it more often; if you want to dial it down, you can; and if you simply don’t like it, you can stop, and it “goes away.” IOW, it’s a short-term commitment. Another pro: nitrous doesn’t impair mobility, so you can still move around.

ACOG’s assessment of nitrous looks more favorable than traditionally injected/intravenous narcotics: “Nitrous oxide is safe for the mother and the baby. Some women feel dizzy or nauseated while inhaling nitrous oxide, but these sensations go away within a few minutes.”

Dr. Ferne Braveman, the director of OBGYN anesthesiology at Yale, explains that nitrous is “a bridge for many patients in early labor who haven’t decided yet if they want an epidural.” Indeed, many describe nitrous as a “less-extreme option” in the pharmacological arm — it’s not as powerful in terms of pain relief (compared to an epidural), but it’s often a huge help!

Okay, moving on…

Non-Pharmacological Pain Relief Options

In the so-called “natural realm,” there is a suite of options that can help relieve pain by resituating your focus (or your nervous system) on something besides your perception of pain. They don’t exactly remove pain, per se, but they can minimize it by moving into the backdrop.

BTW: you can use pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods in combination — there’s no rule that you need to stick to one route or the other.

Because they are not active medications, these tend to have very few/limited risks or side effects, so that’s a huge plus. Some of them involve virtually no “prep work” (looking at you, hydrotherapy), while others entail more preliminary practice and training beforehand (you can’t just decide to “use” hypnotherapy on the day of…). If you’re interested in pursuing any of them, we recommend you talk to an expert about formulating a plan to prepare ahead of time. (No prior experience necessary!) Unmedicated labor/birth takes work — it’s called labor for a reason — and it’s important to know and understand your options in terms of mitigating pain.

An (Obvious) But Very Important Note

EVERYONE IS DIFFERENT, friends. Some women swear by certain of these techniques; others may find they provide little relief. Something might feel helpful early in labor, but not so much later on. What worked wonders for your BFF might feel awful to you, and vice versa. Different strokes, folks. 🙂

This is another reason why it’s worth your time to learn about some different options. I was so sure about hydrotherapy I thought I’d be set, but for me the tub was just… no. I don’t know what it was — something about the positioning, I think — but I just hated it. After four minutes, I was like, get me out of here. That’s just one example; there are a million and one more.

1. Hydrotherapy

Jen Mayer told me that “water is nature’s epidural,” and I love this description. If they are available to you, many women find that laboring in a warm tub or the shower can provide relief.

In one study, about half of women who tried hydrotherapy thought it helped relieve pain; and water immersion may even be associated with shorter labor durations and decreased use of epidurals. (Note that ACOG does not endorse water births… but other organizations, like the Royal College of OBGYN, in the UK, and the American College of Nurse-Midwives, do.)

2. Massage, Body Positioning, & Heat/Cold Therapy

Many women find that body massage and temperature therapies (using heating pads or ice packs) can relieve pain during contractions. Having someone put pressure or lean into your back is an oft-suggested way to alleviate low back pain during contractions, for example. There are all kinds of different tricks and positions, pressure points etc., here, so this is one to ask your doctor/midwife/doula about if you are interested. If you’re giving birth in a hospital, L&D nurses are a wonderful resource, too — ask them!

Also in this category, positioning yourself just so on birth balls or with peanut balls can be very helpful. Likewise, many women find MOVEMENT to provide relief (some even recommend dancing!). You may want to experiment with different positions and movements or rhythms to see what feels most comfortable to you. Remember, everyone is different.

My friend Laurel Gourrier, doula and certified lactation counselor, explained that in her practice, movement is really essential for so many women. She told me that it’s important to trust yourself, take time to try different things, and see how your body responds. She says many of her clients try things like lunges, curb walking, squatting, and dancing, and she said it can help to consider baby’s positioning. The point is to make space for the baby, she said, so you can ask yourself: how am I moving to allow more room for baby to descend?

3. Relaxation & Breathing Techniques

Deep breathing techniques ranging from Lamaze to patterned breathing have a long history and track record in the US. These you would want to learn about and practice beforehand.

Simply establishing a relaxing atmosphere can also contribute to pain relief — this includes simple setting features such as music, dim lights, or aromatherapy. Most hospitals and birth centers allow diffusers and electric flameless candles, or you could use oils for aromatherapy. Keep in mind that your normal sense of smell might be a bit thrown off during labor, so Jen Mayer suggests bringing a couple of different options just in case. Traditional picks include peppermint (good for nausea), lavender (for relaxation), and clary sage (often used to support labor).

Another thing in this department: consider that there is a real connection between pain and fear. “When we are scared or afraid, our bodily response is to run/flight,” Laurel reminded me. Part of the goal with various relaxation and breathing techniques is not only to maximize a sense of calm/control, but also to minimize fear.

4. Hypnotherapy

There’s been a lot of interest in hypnosis for pain relief over the last decade or so — and it’s totally worth checking out. This is definitely a category of pain relief that does demand practice during pregnancy, but the wonderful thing about it is that it’s quite simple to get started, even if you have no experience with meditation or hypnosis. If it sounds daunting (or weird, lol), know that it’s actually pretty darn accessible and has benefits even if you don’t wind up using it during labor.

You could opt to take a formal class, but there are numerous at-home courses and guides for self-study — the practice is essentially listening to recordings that help you learn relaxation techniques and also condition yourself to normalize labor and birth.

Jen Mayer says she loves this option because it’s a great tool to have available, and the practice itself is so beneficial for moms and babies during pregnancy (labor aside). She recommends finding a time daily to practice in a calm, quiet environment where it’s safe/alright for you to fall asleep, such as right before bed.

5. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (aka TENS Units)

TENS units are small devices that hook up to electrodes you place on your body. When you turn the machine on, the electrode pads send mild electrical pulses through your skin, producing a sort of buzzing, tingling, prickling sensation. The premise behind these devices as pain relief is that they stimulate the surface of your skin and almost “trick” your nervous system/pathways into feeling less pain.

During labor, many women use TENS units on the lower back, flanking the spine (another option is acupuncture points). TENS units are cheap, widely available (you can buy them at almost any pharmacy, or ask your OB if they have any that you can rent or borrow) and can be turned on/off and adjusted for intensity level at the flip of a switch.

Tip: doulas suggest using TENS in early labor to start to condition your nervous system to the stimulation and sensations.

*SAFETY NOTE: Obviously, TENS units are incompatible with water.

6. Continuous Labor Support – aka a Doula

Last but not least (!), having what professionals describe as “continuous labor support” can be an enormous source of relief (pain and otherwise…) throughout labor and delivery. Indeed, research shows that having continuous labor support is correlated with fewer assisted deliveries, fewer C-sections, and fewer requests for pain meds. This is not true of “intermittent labor support.”

One of the best ways to secure continuous labor support is by working with a doula. A doula is going to be someone dedicated to YOU who is working outside of the medical system but still tangential to it. Doulas are equipped with both evidence-based resources and community resources and they’re there to serve you and you alone. Most doulas keep a relatively small client roster (only 2-4 per month) and are dedicated to you in a way that your obstetrician and even your midwife won’t (can’t) be.

If you’re interested in hiring a doula, the ideal time frame is in the second trimester, which leaves you plenty of time in the third trimester to begin working together and getting to know one another.

When labor begins, doulas can usually meet you on location or at your home, depending on how things are going, and this is where the continuous support really starts — your doula will be fully present with you for as long as your labor lasts. Doulas have a wealth of knowledge about your pain relief options and will be able to assist you in procuring/experimenting with different varieties of relief and activity (or rest!). They’re a key source of emotional, psychological, and physical support — for both you and your partner, in fact.

L&D nurses are also an amazing resource — we’ve all had wonderful experiences with our delivery nurses! But just due to logistics, even the best nurses will probably only be able to check in on you every 30 minutes or so (doctors about every 3-4 hours). This isn’t to say these professionals aren’t “there” for you — rather, it’s their job to oversee and assist with many women all at once. It’s simply the nature of the job description. A doula, in comparison, is 100% with YOU.

BTW, I think there’s a huge misperception out there (speaking in gross generalities) that doulas are only for women who 100% know they want an unmedicated birth. Not so! Doulas are still a wonderful support system for women who either plan to or later decide to have an epidural. They work with all kinds of clients and they are committed to women and birth, not to any particular agenda or perspective. (For reference, Jen Mayer told me that about a quarter of the clients she works with through Baby Caravan come to her intending to have an unmedicated birth, about a quarter plan to have an epidural, and the remaining half are undecided. That’s a pretty well-rounded sample!)

My point is: a doula’s job is to support you in your birth experience, not to impose some alternate pathway or judgment upon you and your choices. Whether you think epidurals are a crime against humanity or the best thing to happen to women… like, ever, or anything in between, a doula is a great support to consider.

For better or worse, the topic of pain relief during labor tends to be a sticky subject… but it’s interesting that the advice we typically hear from every angle — from OBs, moms, midwives, doulas and the rest — is to keep an open mind and know your options. Heading into things, the only thing you can really know for sure about your upcoming labor is that it’s not going to go how you think it will.

Birth has its own path.

~ Laurel Gourrier

This is why it’s so valuable to have grace for yourself and understand your pain relief options across the board — where we are used to making informed decisions (or at least thinking we are, hah), any attempt to anticipate what you may want or need during labor is like trying to find your way through a maze in the dark. You have to let your eyes adjust; you have to feel your way through things; you have to see where every turn leads you; you have to take one step at a time.

Step one: take stock of things, and get your bearings.

Check. 💪

Thanks to our experts who weighed in:

Many thanks to all of our readers who shared their experiences on FB, as well as:

Jen Mayer, mom of two, financial counselor, doula, founder of NYC doula collective Baby Caravan, and founder of Fully Funded, a financial counseling consultancy specifically geared toward new parents and self-employed people

Laurel Gourrier, MA (special ed), DTI birth & postpartum doula, certified lactation counselor, owner of LG Doula in Columbus, OH, and co-creator & co-host of the Birth Stories in Color podcast

Shana Dowell, MD, Associate Professor of OB/GYN at Vanderbilt University

Erin Zenilman, MD, Anesthesiologist & mother of 2 littles

Selected Resources:

https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/medications-for-pain-relief-during-labor-and-delivery

https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/labor-delivery/topicinfo/pain-relief

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2782642

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4718011/

https://www.cochrane.org/CD000331/PREG_epidurals-pain-relief-labour

Hirschmann-Levy K, Pan S, Cole D. Nitrous Oxide Versus Epidural for Pain Management During Labor and Delivery [32K]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018; 131 127S-127S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000533534.98293.4d.

Earhart KR, Cuff RD, Hebbar L, Goodier C, Mateus Nino JF. . Effect of Labor Analgesia on Fetal Heart Tracing in Term Pregnancies: Nitrous Oxide Versus Epidural [40I]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019; 133 105S-106S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000558817.70612.fc.

Practice Bulletin No. 177: Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017; 129 (4): e73-e89. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002018.

Committee Opinion No. 679: Immersion in Water During Labor and Delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016; 128 (5): e231-e236. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001771.

Cowles S, Norton TJ, Hannaford KE, Foley M. Virtual Reality for Pain Control During Labor: Patient Preferences [14S]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019; 133 206S-206S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000559466.63150.51.

Canestraro AJ, Tussey C, Erickson LP. . Implementation of Nitrous Oxide as an Analgesic Option on Our Labor and Delivery Unit [17L]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019; 133 133S-133S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG/01.AOG.0000559251.92738.fa.

Wong MS, Gregory KD. . Patient Reported Outcomes on the Use of Virtual Reality for Pain Management in Labor [17E]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019; 133 55S-55S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000559009.58037.52.

Farnham T. Reviewing pain management options for patients in active labor. Nursing. 2020; 50 (6): 24-30. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000662352.97953.cd.

Gibson M. JOGNN: Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2021; 50 (4): 369-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2021.04.004.

Nathenson PP, Nathenson S. Nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management. Nursing. 2021; 51 (10): 62-68. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000769888.80327.20.

Leeman, Lawrence, Patricia Fontaine, Valerie King, Michael C. Klein, and Stephen Ratcliffe. 2003. “The Nature and Management of Labor Pain: Part I. Nonpharmacologic Pain Relief.” American Family Physician 68 (6) (Sep 15): 1109-12.

Donald Caton, Maureen P. Corry, Fredric D. Frigoletto, David P. Hopkins, Ellice Lieberman, Linda Mayberry, Judith P. Rooks, Allan Rosenfield, Carol Sakala, Penny Simkin, Diony Young,

The Nature and Management of Labor Pain: Executive summary, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volume 186, Issue 5, Supplement, 2002, Pages S1-S15, ISSN 0002-9378, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(02)70178-6.

Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, et al. Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(3):CD009234. Published 2012 Mar 14. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009234.pub2

Im so glad I had my kids a while ago. Before opioid problems came into play. Had demerol with my first. None with my second, there was no time. Had her in an hour and nineteen mins. With my last two had stadol. Oh that was a life saver!!!!! I feel so bad for moms today, you can’t just get the meds needed. Just given a hard time for pain relief.

Just my option.