Origins of The Upkeep

Lately, I’ve realized that my family is at a critical turning point.

My kids are just 2 and 4 years old, and I’ve never really thought or expected very much of them in terms of “pitching in” around the house or contributing to our family in any meaningful way (besides their being there).

When they were babies, we did everything for them… and that’s just how things continued to progress. Old habits die hard — I’ve kept doing things for them because, well, I just did.

But now, I’m beginning to understand that if I ever want to bring them into the fold, the time to act is now. (Actually, the time to act was “all along,” but there’s no time like the present, as they say.)

“This”^^ sentiment seems almost ubiquitous among American parents these days (right??), but things were not always this way.

There’s no turning back the clock, but maybe it’s worth tapping into some of what most premodern societies understood and practiced: it’s the family’s responsibility to take care of the family’s business (whatever it be).

Changing Families and Dwindling Expectations: A Brief History of The Upkeep

In 2019, David Brooks wrote a provocative piece in The Atlantic called “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake.” He wrote that the gradual splintering of extended, sprawling families into tightly-circumscribed immediate family units (something that happened over the course of hundreds of years) has been a “disaster.”

Yikes.

You see, prior to industrialization, most Americans thought about the concept of family completely differently than we think of it today. Family was a big umbrella. Shoot, maybe it was more like a parachute.

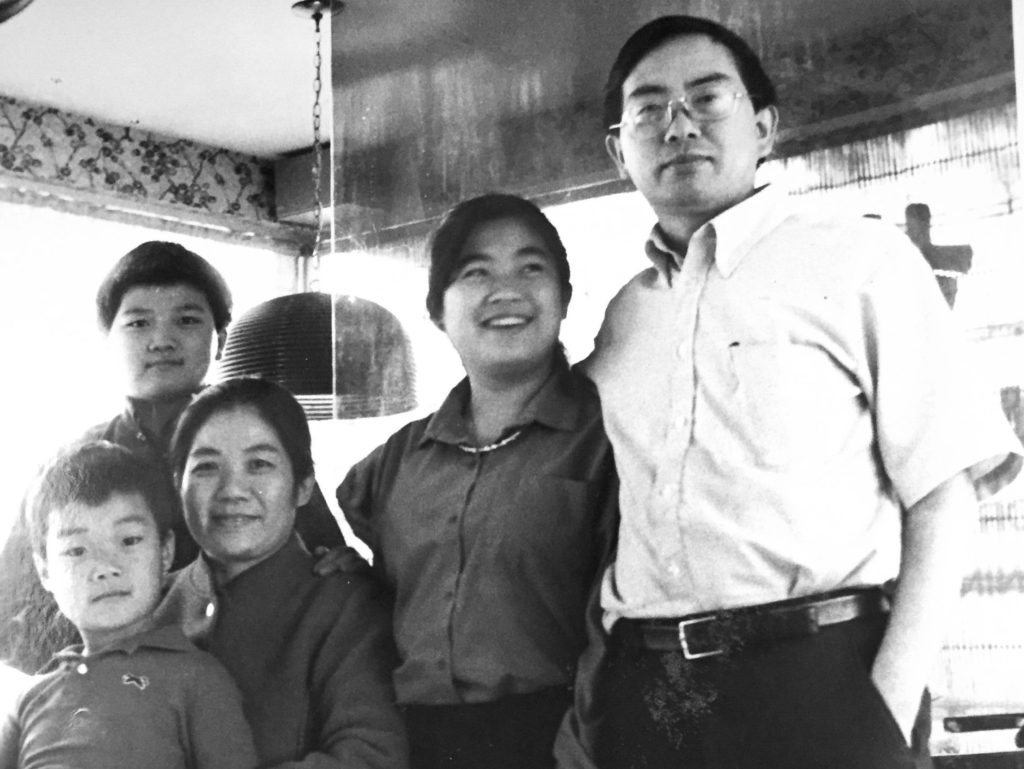

Most people (90%) were integrated into what historians call “corporate families” — they were part of a big, extended, social-familial group that sprang up around… a family business. Usually, the business was farming, but over the course of time other trades and purposes sprang up, too. Some families ran restaurants. Others milled textiles.

Though being a member of a “corporate family” would certainly have come along with challenges of its own, the deterioration of the so-called “family economy” — that is, the family working together as a unit to achieve a common goal or set of goals — has also cost us. Greatly.

“Corporate families” — the large extended families of the past — survived and thrived because everyone contributed, everyone cooperated. They not only shared work, but were also united by a sense of community, a common sense of purpose and value and meaning. Their success was a matter of livelihood and survival.

For most of American history, kids did contribute to the “family economy” — by doing work. Indeed, the expectation was that children would carry their weight, starting as early as 4 years old; and the idea that a child wouldn’t have been put to work on the family farm (or whatever) would have been crazy. And because of no birth control… there was a seemingly endless supply of children.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of factory production and growing cities, the situation got worse for kids. In the late 1800s, young children’s labor shifted, as many were sent to toil for long hours in completely heinous conditions in factories to earn wages for their families.

In the early 1900s, social and political movements fought to end this kind of child labor (it was truly dangerous and abusive), and Progressive reformers helped successfully enact new child labor laws prohibiting children from work.

Plus — public school. (And also — contraception!)

In decades afterward, parents came to think differently about their children. With the advent of family planning, parents’ views toward their children’s roles and meaning in the family dramatically changed: parents grew to value their children more and more for their sentiment and emotional significance, and less for their role as contributors to the family economy.

Nothing wrong with that! But…

Over the course of the twentieth century, the average amount of time an American child spent on housework (or paid work) declined from ten hours per day (what?!) to mere minutes per day (or none at all).

Obviously this isn’t the comprehensive story, but it helps to have a rough understanding of this stuff — of how backlash to the atrocious (and widespread) exploitation of child labor during the Industrial Revolution (combined with a bunch of other social changes, namely birth control) undermined the much longer-standing sentiment that children should contribute to the welfare of the family.

Bottom line: it’s fair to say the pendulum has swung all the way in the opposite direction because many (most?) parents ask very little of their children.

Back to the Present: Finding Purpose in The Family

Families today rarely share the kind of unified solidarity that was pervasive among large extended families in the past. And maybe the state many of us find ourselves in right now gives us clues as to what we may be missing from a foregone era.

Researchers who study happiness (or however you want to think of it) say that lasting individual “happiness” derives from three key things:

- Sustaining meaningful relationships (friends and family),

- Engaging in meaningful and productive work (meaning: anything that makes you feel good to do/have done it — like you’ve earned something), and

- “Faith” in something (anything — not necessarily religion; it could be environmentalism, community service, the church of Sunday football, whatever floats your boat).

Simply put: humans evolved to be most successful as a species when these elements came together in a connected group of people who shared a common goal.

Happy families — we believe — follow this same formula.

They connect with one another, they do things together, they rely on each other, they embark on projects together, and many of them have some sort of shared faith — that is, they share some understanding of what their family stands for.

Although it may seem like a simple question, in the 21st century, it’s anything but: what does your family stand for? And where do your kids stand in that vision? Because ideally, we want them to be more than entitled clients who are reliant on our services.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/53961065/bossbabycover.0.jpg)

That’s what this entire series is about… and now that we have some understanding of how and why The Upkeep came to fall squarely on the shoulders of parents — rather than family units — we can move on and learn about why is it so imperative that we (re)involve our kids.

Let’s keep going!